Sitting in front of a Xerox machine at an advertising agency located above a flower shop on Melrose Avenue, Daniel Ellsberg began the painstaking process of making photocopies of smuggled documents that he hoped would end the Vietnam War.

Earlier that day in October 1969, he had opened the safe in his office at RAND in Santa Monica, where he worked as an analyst, and pulled out the first batch of top-secret papers. He had walked past the lobby guards with his briefcase, casually waving at them.

“I took it for granted that what I was doing was a violation of some law,” Ellsberg wrote in his 2002 book, “Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers.”

His conscience had been eating at him for years. He had been a Marine, a devoted Cold War warrior and a Pentagon consultant who had advised the architects of the Vietnam War, on the grounds that it could thwart the Stalinist dictatorship and promote democracy.

At 38, he was disillusioned by the “hopeless and endless” war that was based on decades of lies — as he expected the public to understand from the newspapers.

It contained 47 volumes, containing 7,000 pages, documenting US military decisions over two decades. They showed that optimistic speeches about the war hid much more serious assessments behind the scenes, and that protecting US presidents from the stigma of humiliating defeat was a major motive for continuing the war.

As Ellsberg wrote in his book, these documents reflected “a repetitive pattern of internal pessimism and desperate escalation in the face of a virtually hopeless impasse and of deception of the public.”

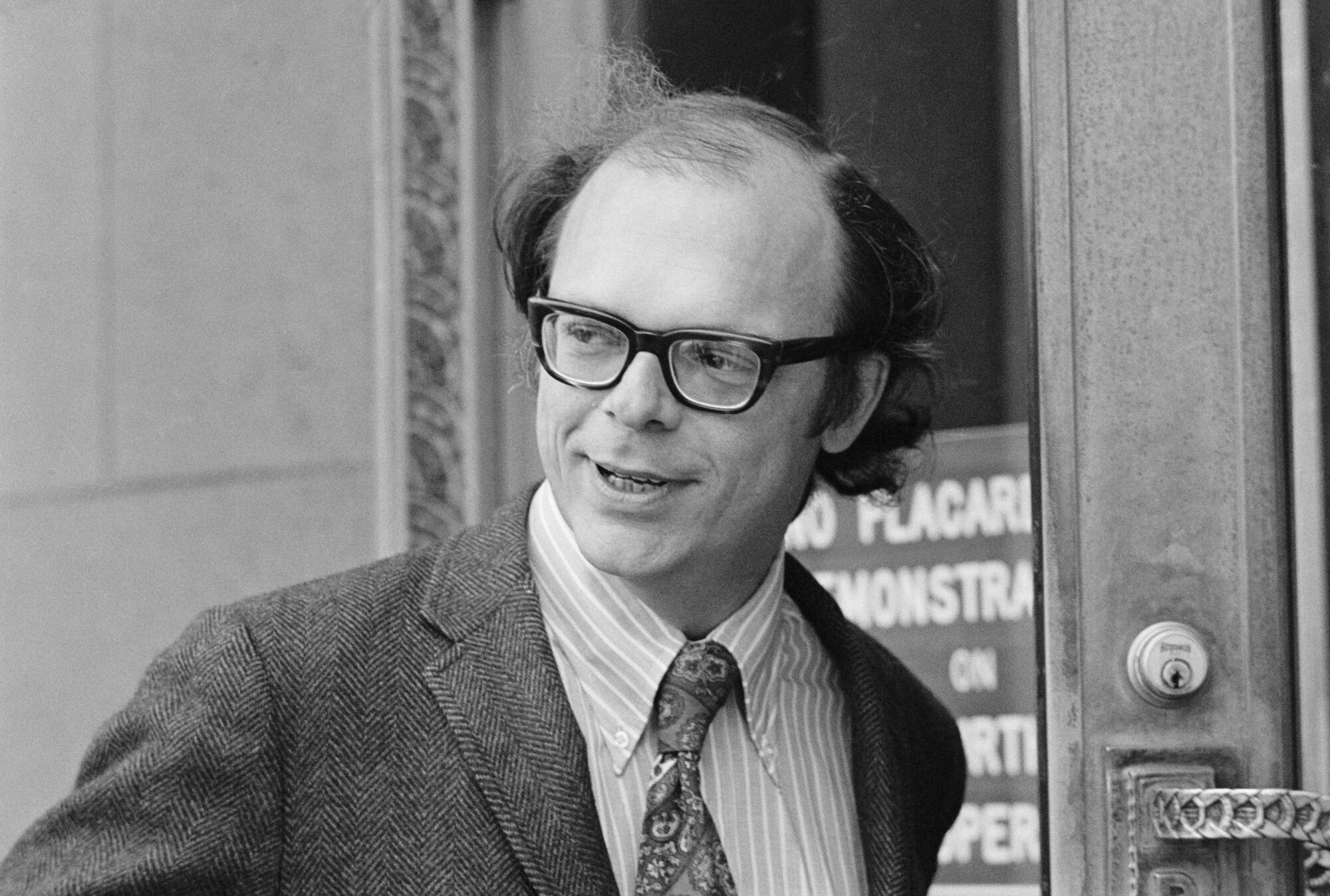

Anthony Russo entered a Los Angeles courtroom where he admitted he had “violated the rules” by copying top-secret documents. He said, “It was my duty as an American citizen.”

(Bettman Archive)

A former RAND colleague, Anthony Russo, had encouraged Ellsberg to leak the paper to the media. Russo’s girlfriend ran an advertising agency and offered the use of her Xerox machine.

Ellsberg made copies after hours, sometimes taking his 13-year-old son along to help. If the government imprisoned him, as was likely, he would be unable to provide for his children. But he saw this as “bigger than me or even my own family.”

Ellsberg submitted the letters to The New York Times, which began publishing them in June 1971. Other newspapers followed, to the anger of the Nixon administration, and the US Supreme Court’s decision affirming the media’s right to publish became a landmark decision under the First Amendment. Steven Spielberg even made a film about it.

The criminal trial that followed in Los Angeles is a less remembered case.

The panic that gripped the Nixon White House and its hatred for Ellsberg would be captured on the Oval Office tapes. To the president’s advisers, Ellsberg was a traitor responsible for “an attack on the entire integrity of the government” and “the greatest catastrophic security breach ever.”

Angered by seeing Ellsberg portrayed as a national hero, Nixon vowed to destroy him, declaring: “We’ve got to kill the bastard.”

The Justice Department has charged Ellsberg under the Espionage Act, and if convicted of conspiracy, espionage and theft of government property, he faces up to 115 years in prison.

When he and co-defendant Russo went on trial in downtown Los Angeles in 1972, the questions loomed large: Did the disclosures threaten national security? Were there circumstances in which the public interest could override the government’s zeal for secrecy?

Daniel Ellsberg, the former Defense Department researcher who leaked top-secret Pentagon documents to the press, testifies before an informal House panel investigating the documents’ significance in 1971.

(associated Press)

Mark Rosenbaum was a student at Harvard Law School when he took leave to assist the defense team.

“To my knowledge, this is the first trial in the country’s history that really examined how the government lied to its people,” Rosenbaum, a longtime public interest lawyer in Los Angeles, recently told the Times. “Most people took everything the government told them as truth. This trial laid bare that. In 2024, it’s hard to remember how revolutionary and revelatory that was.”

Rosenbaum said the trial involved not just American foreign policy but “the whole system of classifying documents.” “We showed that much of what was classified as secret or top secret was actually an attempt to suppress politically embarrassing material.”

The defense team believed that Nixon’s DOJ wanted the trial to take place on the West Coast in order to find favorable jurors from the aerospace industry, which was heavily dependent on the Defense Department. Rosenbaum recalled that the jury was selected from “a lot of retired government employees” who were adamant about conviction.

“You can feel bad feelings,” he said.

But appellate arguments caused months of delays, and a new jury was selected that appeared more favorable to Ellsberg’s side.

There was little disagreement over the facts. No one disputed that Ellsberg had taken the papers and photocopied them. But the defense argued that the disclosure posed no threat to national defense, that the documents belonged to the previous presidential administration, and that much of the material was in the public domain anyway, although in scattered form. And before giving the papers to reporters, Ellsberg had tried unsuccessfully to make them public by giving them to members of Congress.

Daniel Ellsberg, the lead defendant in the Pentagon Papers case, addresses the crowd after an anti-war parade in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1972 that ended at the state capitol.

(Rusty Kennedy/Associated Press)

But defense attorney Charles Nason told the judge that Congress was “in the grip of the executive branch,” adding: “There was no other path than the one chosen by the defendants.”

In a recent interview with the Times, Nesson, 85, said another of the defense’s thrusts was that Ellsberg had not actually stolen government property. He had photocopied documents and returned the originals. What he did was to disclose information — but “the government doesn’t have the information.”

In late April 1973, during the trial, U.S. District Judge Matt Berns handed Ellsberg’s lawyers a shocking report he had received from the Justice Department. A White House-directed team of operatives, known as “the Plumbers,” had broken into the Beverly Hills office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist to look for compromising material.

Rosenbaum said that late one night he and another young lawyer went to the small home in East Los Angeles of a woman who cleaned a psychiatrist’s office and saw the burglars. The lawyers had an issue of Time magazine with a picture of Watergate conspirator G. Gordon Liddy. Rosenbaum said the cleaning woman recognized him as one of the burglars.

“That started to open things up,” Rosenbaum said.

In another embarrassing revelation for the government, the FBI admitted that it had recorded Ellsberg’s voice in wiretap surveillance several years earlier–and that the transcripts had disappeared.

But what ultimately derailed the case was the Nixon administration’s unfair treatment of the judge. The defense learned that Judge Byrne had visited the president’s San Clemente home in the middle of the trial and that Nixon had offered him a job running the FBI.

Nesson said this was tantamount to Nixon “trying to bribe the judge to get a conviction.” It was “the pinnacle of the kind of misbehavior that Ellsberg described.”

Judge acknowledged the San Clemente meeting, but said he declined the FBI job. Nesson said he received a call soon after that Judge had been seen in a park with Nixon aide John Ehrlichman.

“I knew he was the killer,” Neeson said. “Eventually the judge was cornered.”

Defense lawyers debated whether to inform the judge in court or inform him privately. Neeson opted to do so by phone in his chambers.

“I have never regretted having shown the professional courtesy of informing him that he was about to be killed,” Neeson said.

In May 1973, Byrne declared a mistrial and dismissed all charges against Ellsberg and Russo on grounds of government misconduct, stating: “Bizarre events have incurably infected the prosecution of this case.”

Daniel Ellsberg smiles with his wife Pat as they leave the Federal Building in Los Angeles on May 11, 1973. The incident occurred shortly after the judge in the Pentagon Papers case dismissed all charges of espionage, theft and conspiracy against Ellsberg and his co-defendant Anthony Russo.

(associated Press)

The jurors arrived at the office set up by the defense lawyers in downtown Los Angeles. It was clear that many of them were in favor of acquittal.

The leaked papers and the resulting trial fueled distrust and suspicion of the government, which became even more intense after the Watergate scandal broke.

Did Ellsberg’s leaks help end the war? As Ellsberg argues in his book, fighting the Watergate scandal prevented Nixon from blocking a congressional resolution to stop the bombing. And Nixon’s attempts to cover up the criminal exploits of White House operatives – such as the burglary of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office – led to his disgrace and resignation.

Rosenbaum said that because of strict laws about revealing government secrets, Ellsberg’s defense would have little chance of holding up in court today.

“Today it will be open and shut in favor of the government,” Rosenbaum said, because now “the only burden is on the government to prove that the document is confidential, and that will be the end of it. ‘Was the document confidential?’ ‘Yes.’ That’s it.”