By the time 38-year-old Caryl Cheesman was hanged on the morning of May 2, 1960, he had been on California’s death row for 12 years. His brooding, rugged features were recognizable around the world, his name a rallying cry from South America to the Vatican.

He was mid-century America’s most arch-punk intellectual, high school dropout and autodidact, who wrote and published four books while waiting to die. He bragged colorfully about his abundant crime, but swore he was innocent of the charges that brought him infamy.

They inspired literary praise, hunger strikes, protest songs, diplomatic crisis, and a crisis of conscience for the state’s Catholic governor.

He is mostly forgotten today. But Cheesman’s case dominated the death penalty debate for years. Apart from his skills as a writer, his gift for publicity, and the length of his stay on death row – a record at the time – his case was unusual in that he was not convicted of murder or even charged with No allegations were even made.

However, he became notorious as the terror of the streets of Lovers. During a four-day period in late January 1948, the Red Light Bandit – so called because his late model Ford was equipped with police-style flashing lights to deceive victims – held joints at gunpoint on hills in Malibu and Laurel Canyon. Robbed. And secluded roads above LA and Pasadena.

In one attack, the gunman forced a woman to walk with him to his car — a distance a prosecutor says made 22 feet difficult due to the effects of polio — and forced her to perform oral sex. Two nights later, the gunman kidnapped the 17-year-old girl, drove her around town for hours and again demanded oral sex. Little will be charged in those two incidents under the state’s Lindbergh Law, which allows the death penalty for kidnapping with bodily injury.

After a high-speed chase, police caught Chessman in a stolen Ford linked to the Redondo Beach stickup at Sixth Street and Vermont Avenue. During interrogation, Chessman implicated himself in the robber’s crimes, although he claimed that the police coerced the confession out of him.

Devastating to Chessman, whose arrogance and hunger for the spotlight were one of his most important qualities, he insisted on acting as his attorney. He cross-examined sexual assault victims who identified him as their attacker. The teenage girl looked straight at him and said, “I know it was you.”

Caryl Cheesman in 1958, on the 10th anniversary of his arrest. By then, he was a bestselling author.

(Los Angeles Times)

“He liked to claim to be a great criminal, but great criminals don’t get caught,” Theodore Hamm, who wrote a book about Chessman, told The Times in a recent interview. “He thought he was the smartest person in the room and that he could outwit any prosecutor and win over the jury. “Obviously it didn’t work out in his favor.”

Jurors convicted him of 17 counts of crime that lasted a month. He was 26 years old and smiling sheepishly as the judge handed down two death sentences. His 12-year legal battle to escape San Quentin’s gas chamber – which he called “that ugly green room” – attracted worldwide attention, as did his prison writings.

His 1954 memoir, “Cell 2455, Death Row: A Condemned Man’s Own Story,” became a bestseller.

He described his face, with its damaged nose and large features, as “one who has seen too much, a young-old face, scarred by violence… a violent face that seems to have been thrown into the gallery of the doomed.” I have found my rightful place.”

Born in Michigan and raised by devout Baptists in Glendale, he realized the “shame and degradation” of poverty when his father’s business venture flopped.

He wrote of his childhood in which he learned to despise society and its rules, concluding that “you got away with anything you were smart enough to avoid.” He spent years in juvenile detention, reform school, and prison.

Caryl Cheesman’s case inspired petitions and protests from Los Angeles to South America. At the time, his 12-year stint on California’s death row was the longest on record.

(Ray Graham/Los Angeles Times)

“He loved playing cops and robbers,” he said, and he became an expert informant. Arrested for theft on his 17th birthday, he told police “one trivial lie after another” and “developed a foolproof technique: near-truths, half-truths, but never the whole truth.”

He described himself as “a smiling, anxious young criminal psychopath who was in bondage to his psychopathy.” With “hate and deceit as the tools of their trade”, they closed bordellos, liquor stores, and gas stations. In the encounter with the police he shouted, “Come on, you dirty bastards, let’s play!”

His long criminal record has never been in dispute, but it is easy to suspect that it may have fueled some of his illegal exploits. There was a sense of self-dramatization in his stories. He understood the tug of crime’s appeal to attention-seekers – and society’s weakness for outlaw heroes.

He wrote, “All you have to do is be a violent, rapacious, murderous bastard and your fame is assured.” “One of the peculiarities of the classes is their evil tendency to glorify scoundrels and scoundrels.”

In some circles, his death row writings were enthusiastically welcomed. According to the New York Times, it was an “outstanding contribution” to criminology, and as Partisan Review magazine said, evidence of “liberation of the self.”

“He influenced New York intellectuals,” Hamm said. In the post-war period full of optimism about the prospects of reform, “he stood up for a rehabilitated prisoner, and the proof of his rehabilitation was his lucid explanation of what was prevalent in pop psychology about reform.”

Eleanor Roosevelt, Ray Bradbury, and Aldous Huxley signed a petition to spare Chessman. Petitions poured into the office of Gov. Edmund “Pat” Brown, a Democrat who believed Cheesman was guilty but abhorred the death penalty on religious grounds. In 1959, he refused to grant Cheesman clemency, saying that he showed no remorse but “strong arrogance and contempt for society and its laws”.

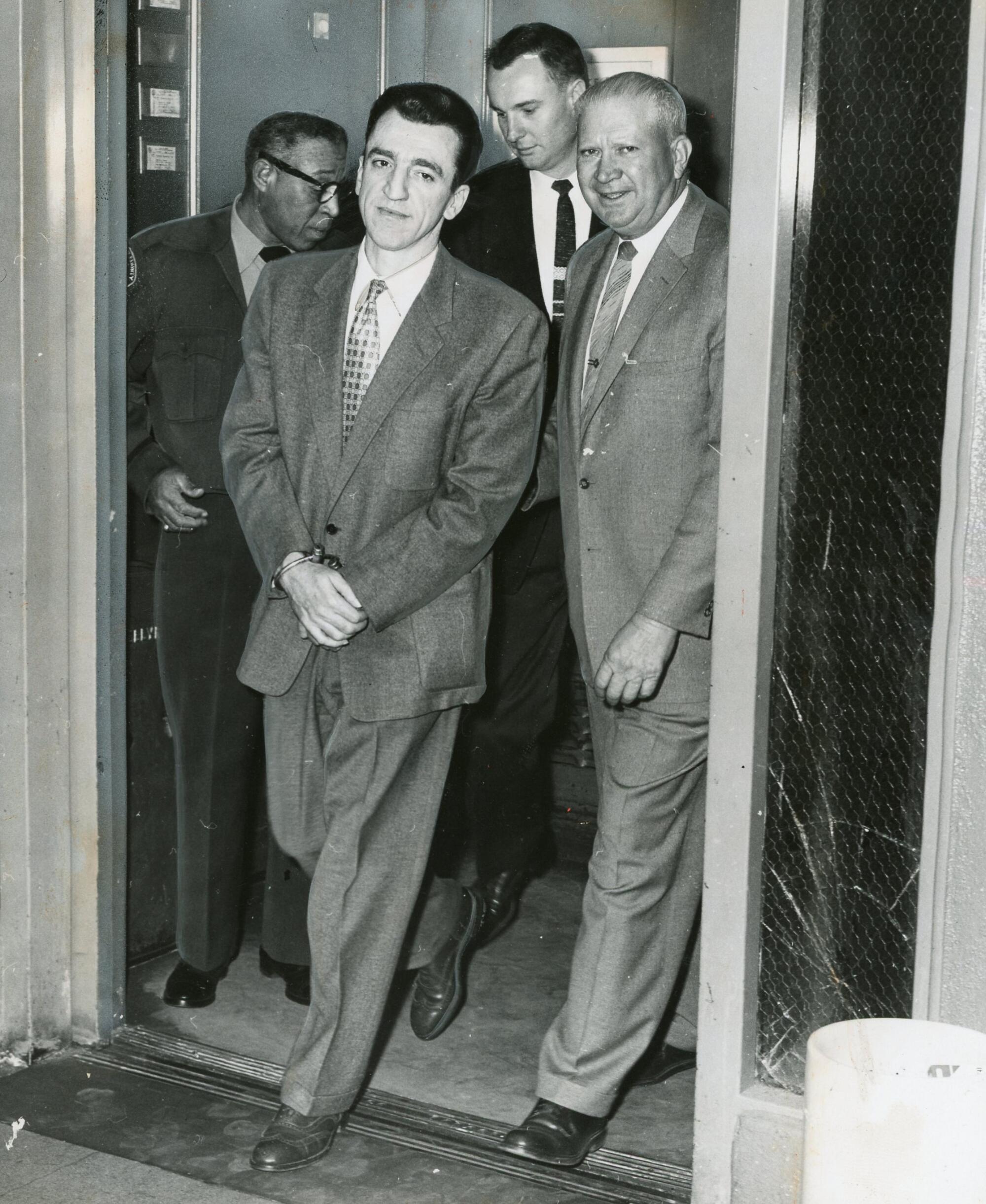

As Caryl Cheesman was being led back to his death row cell in San Quentin, he insisted on representing himself at trial.

(Los Angeles Times)

Chessman made the cover of Time and was favored in editorials around the world, from the Vatican newspaper to London’s Daily Mail.

Ronnie Hawkins recorded a protest song, “The Ballad of Carol Chessman”, whose lyrics expressed the sentiments of many sympathizers: What they are saying may be true, but what would be the benefit of killing him? Let him live, let him live, let him live. I am not saying forget or forgive… If he is guilty of his crime, keep him in jail for a long time, but let him live, let him live, let him live…

The Los Angeles Times was not among the sympathetic voices. An editorial condemned the “save-chess madness”, arguing that the real outrage was the legal maneuvering and political weakness that had delayed his execution.

“The smiling, boastful, quick-witted – and vivacious – Chessman, guilty of unspeakable crimes, is a heavy reproach to the conscience of the state,” the Times argued, adding that “his supporters were ignorant of the gravity of his crimes” because the newspapers did so. Don’t dare publish the gruesome details.

In her memoir, Caryl Cheesman describes herself as “a violent face” who appears to have found her rightful place in the gallery of the doomed.

(Edward Gamer/Los Angeles Times)

The US State Department warned Brown that Chessman’s execution could provoke protests during President Eisenhower’s upcoming visit to Uruguay, where the prisoner was a cause célève. And Brown received a call from his 21-year-old son, Jerry, a recent seminarian and future governor, who pleaded with his father to spare Chessman’s life.

The governor ordered a reprieve, but when he asked lawmakers to impose a moratorium on the death penalty, they refused. The anti-Chesman mob burned an effigy of Brown and publicly insulted him and his family.

Prison officials tried to strangle Chessman, but he continued writing and his pages were smuggled out. Eight times, he was assigned dates with the Green Room, and eight times he won with a delay.

Ultimately, Brown claimed he was powerless to stop the execution, as the state Supreme Court had ruled against Chessman.

Until his death, Chessman denied that he was the Red Light Bandit. He suggested he knew who the “real” robber was, but refused to say. One of his last comments was, “I hope that my fortune has contributed something to the abolition of the death penalty.”

The circumstances of his execution gave further ammunition to critics who considered the system capricious and absurd. That day, Chessman’s lawyers persuaded a judge to issue a summary restraining order, but the judge’s secretary misdialed the jail to relay the news – and by the time the call came, Chessman was dead. Was.

Cheesman wanted his remains to be interred with his parents, but Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale refused on the grounds that he was “unrepentant”.

The case energized opponents of the death penalty and reformers used it to push for revised kidnapping laws. California executed another prisoner under the Little Lindbergh law in 1961, the last execution for a nonfatal crime, and the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the death penalty 11 years later (although it was reinstated ). In 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom announced postponement To be hanged in California.

The case impacted Brown’s political career. When Ronald Reagan defeated him for governor, Brown knew that his opposition to the death penalty had played no small role. Brown believed that Chessman was an evil and arrogant man, yet his failure to do more to save him would prove to be a source of deep regret.

Brown said decades later, “For an elected official there were political calculations to be made with the programs he expected to implement for the common good.” “I believe strongly in all that. I also believe that I should have found a way to save Chessman’s life.”