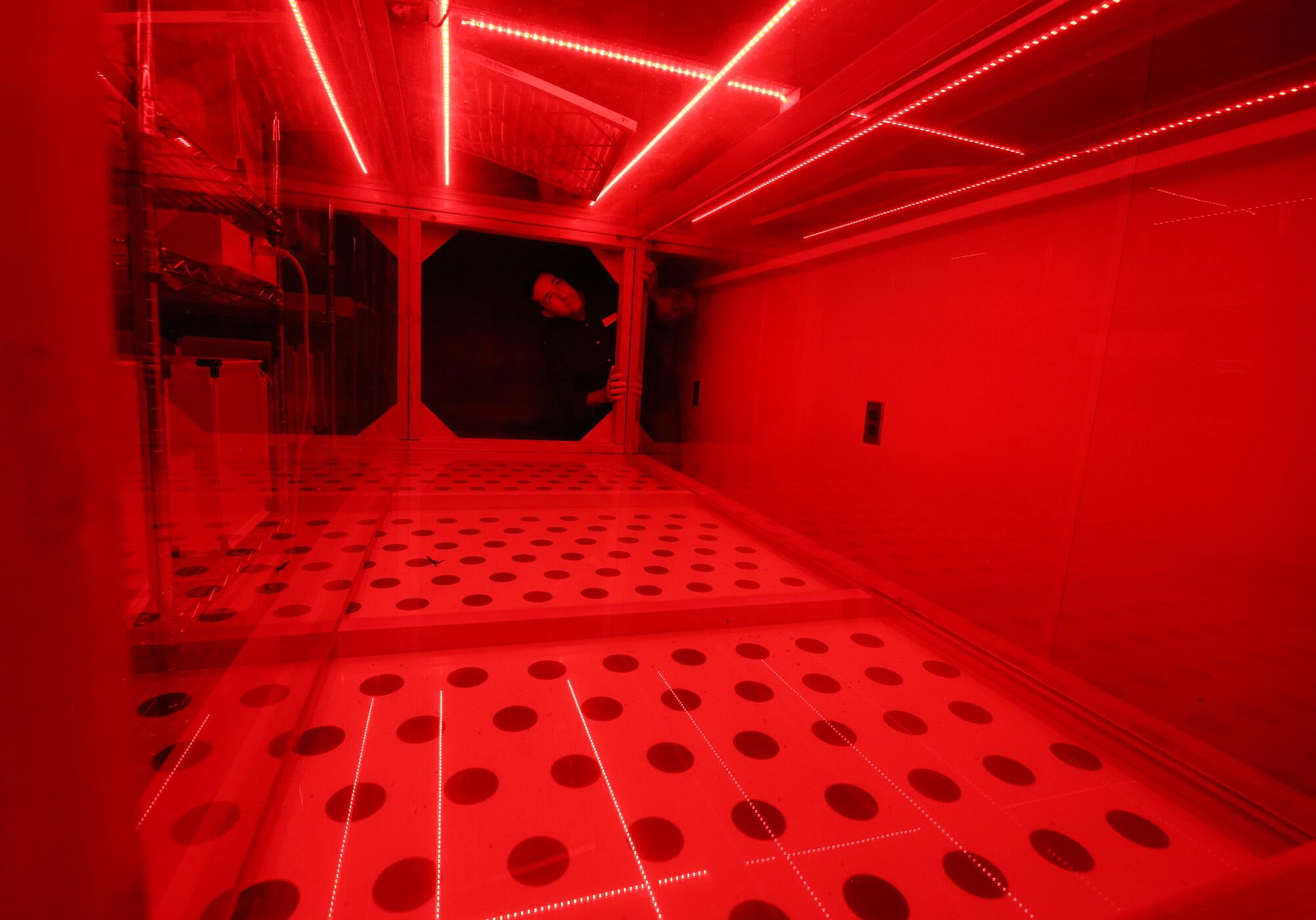

In a windowless shack on the far outskirts of Fresno, an ominous red glow illuminates a laboratory filled with X-ray machines, shelves of glowing boxes, a quietly humming incubator and a miniature wind tunnel.

Although the scene seems straight out of a sci-fi movie, it’s actually part of an experimental program to prevent a harmful almond insect from successfully mating.

California almond growers are in trouble Fall in walnut prices And due to rising costs, pests have added to their problems.

Each year, the navel orange worm eats about 2% of California’s almonds before they reach grocery store shelves. Last year it was almost double.

An insect net hangs from the branch of an almond tree.

(Gary Kazanjian/For The Times)

While that may seem small, if you do the math, “this pest will cause millions of dollars in damage,” said David Haviland, Kern County farm advisor at the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. “And this is despite the control methods that people use,” he said.

California produces 80% of the world’s almonds, yet in 2022 The production value of walnuts fell 34% compared to the previous year.

Scientists say climate change could make the naval orangeworm problem worse, as warmer temperatures allow the moths to reproduce more rapidly. (Despite its name, this insect does not bother citrus farms on a large scale and is actually a pest.)

Traditionally, walnut farmers have dealt with the pest with chemical pesticides, or by destroying the almonds – “mummies” – that remain after harvest. Mummies are a favorite winter shelter for insects.

However, research is increasingly showing that chemical pesticides are harmful not only to the environment but also to people. a new study found that the effect of ambient pesticide use on cancer incidence “may be equivalent to that of smoking.”

“When you have to wear a spacesuit to basically plant something, you definitely think, ‘This is not cool,'” said Houston Wilson, an entomologist at UC ANR’s Kearny Agricultural Research and Extension Center and the mastermind behind the science. Is.” -Fi Shack.

“On the whole, people want to move away from chemical controls,” he said.

So farmers and researchers are searching for other non-pesticide alternatives.

Removing almost every last mummy from every tree in an orchard can be effective, but since this must be done manually, it may be too expensive and complicated for some growers.

Another tactic that has been in use since around 2010 is to cover gardens with deceptive levels of sex pheromones to confuse horned moths – a technique known as “mating disruption”.

But with limited budgets and fears that conditions for the insects will worsen due to climate change, researchers are studying another yet-to-be-proven approach: sterilizing about a million moths a day with radiation and dropping them out of planes. .

Houston Wilson looks at trapped moths at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Parlier, California.

(Gary Kazanjian/For The Times)

The idea behind the technique is that by overpopulating gardens with sterilized insects, they will mate with fertile insects and produce no offspring, reducing the overall population.

The simplest way to sterilize insects is to use radiation. Since their reproductive genes mutate rapidly, the right dosage may leave them relatively unharmed but unable to reproduce.

On request of almond and pistachio farmers, California Department of Food and Agriculture He has been working with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service since 2018 to obtain sterilized moths from the Phoenix laboratory.

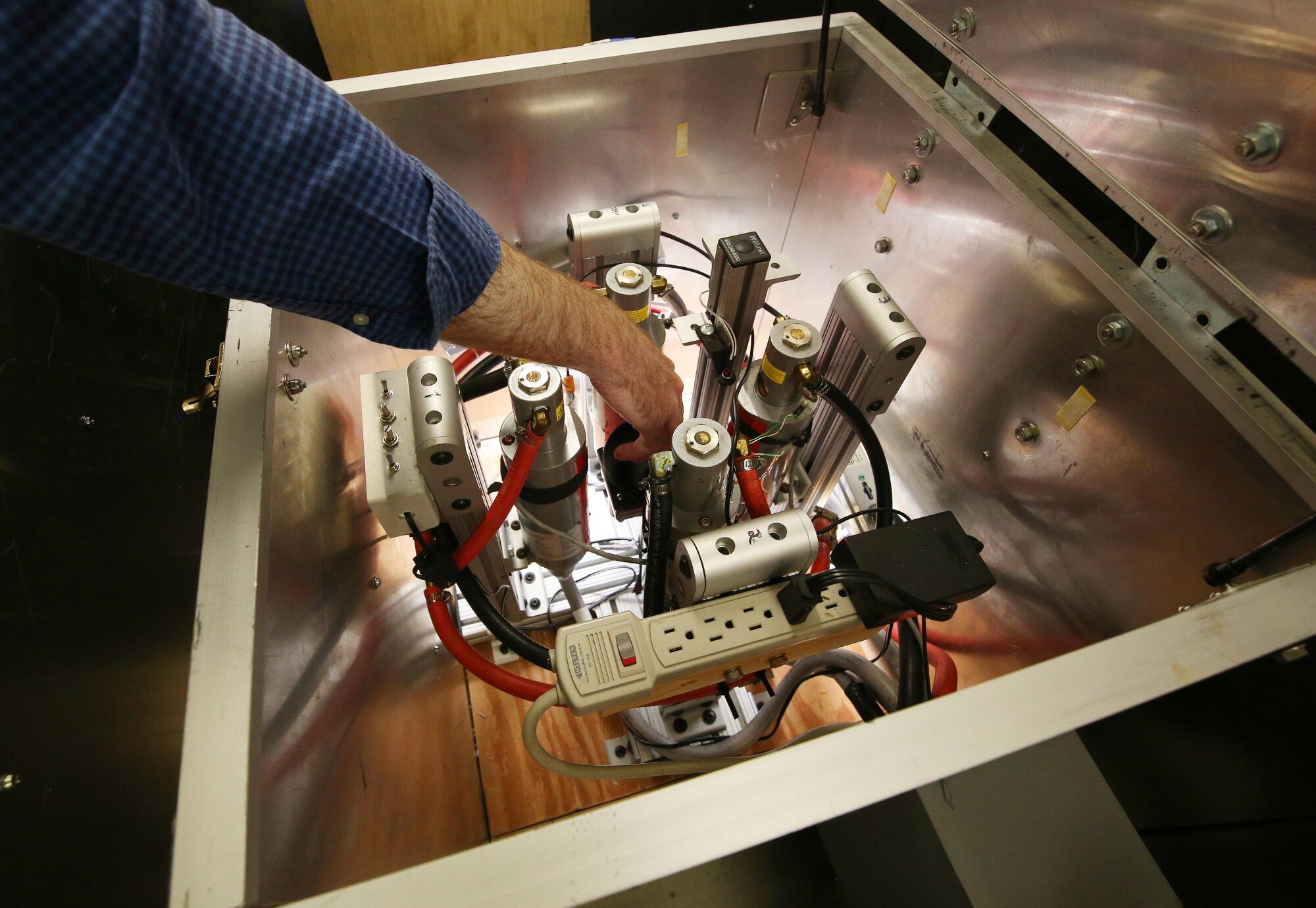

An X-ray machine designed to sterilize moths is shown at the Kearny Agricultural Research and Extension Center.

(Gary Kazanjian/For The Times)

The lab sterilizes about 750,000 moths a day, then chills the moths, puts them to sleep and ships them to California. Insects are dropped from airplanes hundreds of feet in the air. Too sleepy to fly often causes the insects to crash into hard ground or almond trees.

From there, the survivors have only one thing to do: have sex.

Through this testing program, the USDA hopes to perfect the best ways to reproduce the moths in the laboratory and give them the right dose of radiation that will dehydrate them but not seriously injure or disorient them.

However, the program has still not made a significant dent in the insect population, as they cannot produce enough sterile insects.

Right now, researchers are finding only a few sterile insects in their traps for every hundred wild fertile moths. For the technology to be effective, they would need to deploy dozens of sterile insects for each wild insect.

Anissa Bell Guzman counts moths at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Parlier, California.

(Gary Kazanjian/For The Times)

Matthew Aubuchon, national policy manager for the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, estimated that with enough staff working around the clock the Phoenix facility could produce 8 million moths per day.

Although opening more facilities in California would help, the program uses cobalt to produce high-energy radiation to sterilize the bugs—which is expensive and requires the lab to take extensive safety and security measures.

Wilson’s science-fiction hut in Kearney may contain a solution that is cheap and easy to build at scale.

Instead of using cobalt or other radioactive materials, Wilson’s team uses an X-ray machine to irradiate the insects. (Unlike radioactive material, an X-ray machine will not emit radiation when turned off.)

Then, the team puts their X-rayed insects and Phoenix’s sterilized insects through a series of tests to determine which methods produce the healthiest, sterile moths.

The tests involve attaching kites to the end of a stick suspended in the air. As the moths flutter around, the stick spins like a carousel and researchers record how well they can fly.

Houston Wilson investigates an insect wind tunnel as researchers look for innovative ways to manage an invasive almond insect.

(Gary Kazanjian/For The Times)

Researchers also place moths in a wind tunnel and release sex pheromones to see whether the aroused insects are able to detect the smell. (Unfortunately for insects, there are no potential mates at the end of the tunnel.)

Although the team has not yet produced enough Leave it in the almond field. That’s actually how good they are at finding fertile moths to mate with.

Houston Wilson looks at a web of navel orange worms in an almond field in Parlier.

(Gary Kazanjian/For The Times)

However, Kearney researchers may be in a race against time.

Scientists say that it is possible that due to climate change the weather will continue to favor moths. The metabolism of navel orange insects – like that of many agricultural insects – is linked to temperature. The warmer it is, the faster they grow and reproduce.

A 2021 study found that the moths, whose life cycle can be as short as only a month, may be able to give birth to another generation each summer before being stored in nuts for the winter.

“For each additional generation, their population is growing faster,” said study author Tapan Pathak, a professor at UC Merced.

“If this additional generation…coincides with the harvest,” Pathak said, “then they become unmarketable.” This is a huge economic loss.”

However, the food web is complex, and just because warmer weather benefits moths on paper, doesn’t mean the moths will rise to the top.

Each year, navel orange bugs eat about 2% of California’s almonds before they reach grocery store shelves.

(Gary Kazanjian/For The Times)

“The navel orange worm can be a nightmare… but it may also be less of a problem because everything it eats benefits more from the heat than the navel orange worm,” Haviland said. “The crystal ball is certainly not clear enough to know what will happen.”

The researchers emphasize that successful pest control will require multiple measures.

“What we have learned through integrated pest management is that adopting different approaches at the same time or simultaneously gets results for growers,” Aubuchon said.

This tried-and-tested non-pesticide method has been used by growers for as long as moths have existed. Unannounced arrival in the 1940s Just make sure that all the almonds are either harvested or destroyed by the time winter arrives.

But for this method to be effective, there should be no more than two almonds left on each tree in the garden. This may be difficult to achieve in wet weather.

Rain causes almond branches to become wet and flexible, making it difficult to break almonds using an industrial shaker. It may also be difficult for machines to get close to the trees due to the moist soil.

Instead, workers must use poles to manually crack the almonds. As effective as it is, rising labor costs mean some farms cannot afford it.

Anissa Bell Guzman counts moths at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Parlier.

(Gary Kazanjian/For The Times)

While researchers say there are still many hurdles to overcome before the sterile insect technology becomes widely effective, they say it has great potential.

“You’re actually managing an insect by preventing it from being produced in the first place,” Haviland said of both the sterile insect technique and pheromone mating disruption. “To think that something like this was possible 10 or 15 years ago – no one could have imagined that producers would use such innovative technologies.”