It was June 7, payday at Reclaim-Possibility, a 22-bed home in South Los Angeles that houses men released from prison who might otherwise end up homeless.

Once again, owner Kalen Hadley had to tell his 10 employees they wouldn’t be getting paid.

The reimbursement cheques due on the first of July from their funding agency, the Amity Foundation, had not yet arrived.

“It’s really not a pleasant conversation,” he said.

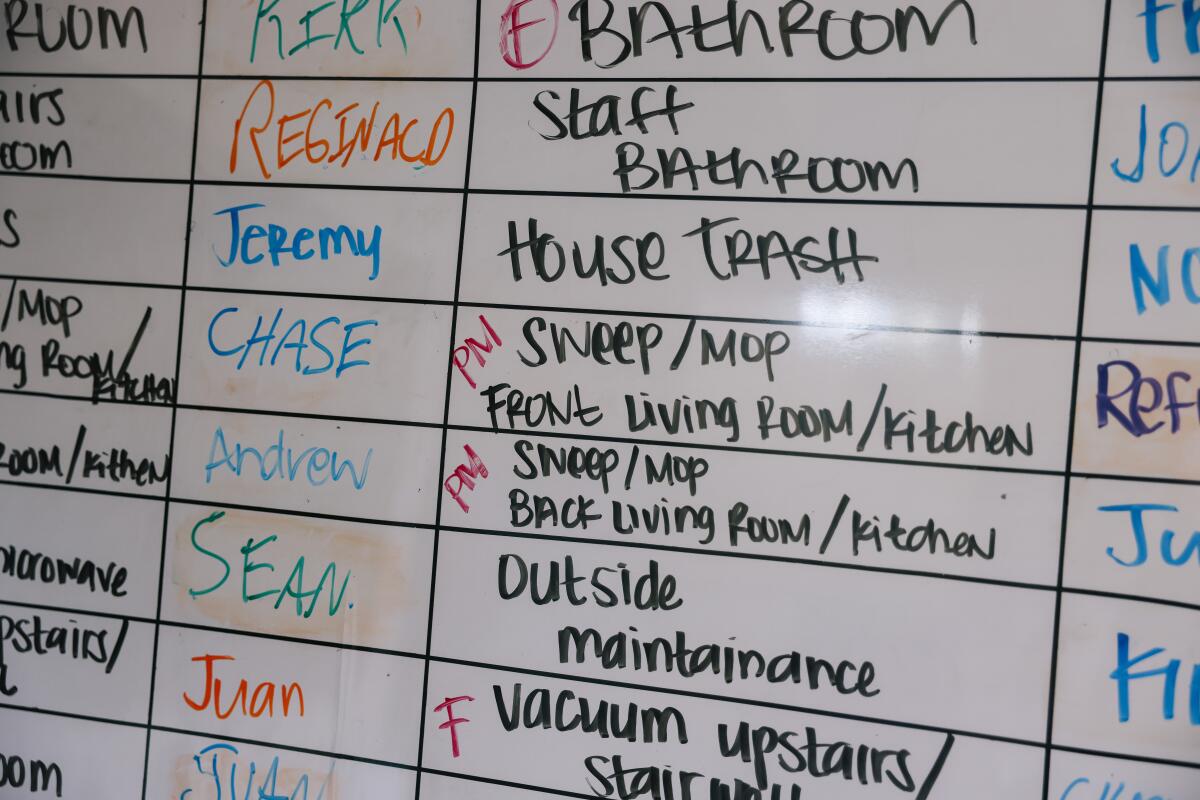

Because of the constant costs and unstable payments, nonprofit owner Kaleen Hadley said she felt like she had no choice but to use predatory lenders. Above, a list of the work in one of her transitional homes.

(Dania Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

Like many nonprofit providers with government contracts, Hadley is constantly in arrears because of a complicated reimbursement scheme that holds up payments 60 to 90 days after services are billed.

The invoice, which varies week to week depending on the number of employees they have, goes to their two funding nonprofit agencies — Amity and HealthRight 360 — then to the Los Angeles County Probation Department and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Payments go back to the agencies, then to Reclaim-Possibility, sometimes by payday, often not.

Rent, salaries and utility costs were all fixed, but payments were based on the number of clients he had at any given time, so Hadley felt he had no choice but to turn to predatory lenders.

“They give you $30,000. You make $43,000 back by paying every day, which is a really big deal,” Hadley said.

As services relating to the homeless have grown enormously in recent years, shortfalls in funding have become a problem. A heavy burden on a billion-dollar homelessness system This is impacting hundreds of service providers and the largest organizations like Reclaim-Possibility.

Testifying on the crisis before the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors last month, People’s Concern Chief Executive Officer John Massery said his $85 million operation would have to borrow $8 million to cover the delay from billing to reimbursement. Money earmarked for services goes to interest.

Kalen Headley (left) works in his office Tuesday while a resident exercises at one of two transitional homes Headley operates for men being released from prison.

(Dania Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

To mitigate this problem, supervisors on Tuesday voted to allow county staff to provide quarterly cash advances from Measure H homeless sales tax proceeds to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, which it can forward to its contractors as cash advances. LAHSA would then reconcile the invoices.

But this influx of upfront cash won’t reach Hadley, whose reimbursement is routed through the criminal justice system.

Now, an alternative plan is emerging outside the government to give Hadley and others like him a reprieve. It’s a project Future Communities Institute, A specialized nonprofit organization that bills itself as an “action-tank” that finds solutions to complex challenges by bringing together academia, government, technology, and philanthropy to test-launch new strategies.

Justin Szlasa, director of Future Communities’ homelessness initiatives, is pushing a targeted solution that would get money directly into the hands of small service providers like Hadley when they need it.

It is based on factoring, an ancient commercial practice in which a company sells its accounts receivable – what it owes but hasn’t yet paid – at a discount in order to obtain cash.

“Almost every industry has this kind of bridge financing that helps things flow smoothly and work better,” says tech entrepreneur Justin Szlasa, pictured at right with Kalen Hadley. “And it’s time for the nonprofit sector, particularly homeless services, to have this in Los Angeles.”

(Dania Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

“Almost every industry has this kind of bridge financing that helps make things go smoother and work better,” Szlasa said. “And it’s time for the nonprofit sector, particularly homeless services, to have this in Los Angeles.”

Szlasa, A. (2005). Film Producer and tech entrepreneur, worked for many years as a volunteer, board member, and then transitional executive director Selah Neighborhood Homeless Coalition before making a full-time commitment to end homelessness at Future Communities, which is financially sponsored by Edward Charles Foundation.

He found inspiration in New York when he was assigned to work on the funding gap problem.

“I looked for other solutions to this problem and found that Fund for New York City,“We’ve been working on this for several decades,” Szlasa said.

Funded by philanthropy and the City of New York, FCNY has raised more than $1.65 billion through no-interest bridge loans since its founding in 1976, recycling the funds after the loans are repaid.

Szlasa is seeking funds from the government and philanthropic donors to create a working capital fund. Unlike factoring, which involves the sale of assets, this fund would provide interest-free loans that would be repaid when reimbursement comes in.

They have set a modest goal of raising about $650,000 for installation and a year of operations to prove the concept and sort out operational details.

“We want to get the ball rolling and show that it’s going to be operationally efficient,” he said, so “we can provide loans. We can provide relief. We can get the money back. And we can build the infrastructure to provide the capacity.”

A year’s worth of operations would cost about $450,000, including one-time work to write staff and contracts and install loan servicing equipment.

“We think you need at least $200,000 of capital to show that this will work,” Szlasa said. “With that, I can take out a $50K loan. I can get paid back and get this thing going.”

Kalen Headley, left, is a former three-strikes lifer who earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees. During his sentence, he came to a realization: “If I didn’t make some changes, I’d be walking around in those 1,000 square feet for the rest of my life.”

(Dania Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

A similar concept is already being tested through a fund created to help organizations supported by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation. The Nonprofit Finance Fund, a community-oriented financial institution that manages the program, has so far made 17 loans averaging $480,000. These loans, made to organizations with budgets of $2 million to $50 million, are interest-free but are similar to traditional loans in terms of the time it takes to get the money out, said Annie Chang, vice president of community engagement.

Szlasa’s goal is to create a more rapid process, so that money can be received in no more than three days, especially for smaller organizations.

“Groups that have the least ability to access credit, like the Klans of the world,” he said. “The aim is to help groups that are really struggling in this way.”

Timing is crucial for Hadley, 59, a three-term life convict who turned his life around during his 25 years in prison and earned a bachelor’s degree before a law change cleared the way for his release in 2014.

“During my life imprisonment, I realised that if I didn’t make some changes, I would have to roam around in that 1,000 square feet space for the rest of my life,” he said.

Subsequently, she earned a master’s degree in social work and did outreach and consulting work for several agencies in the Los Angeles area before deciding to start her own business.

His timing couldn’t have been worse. He opened the first of his two halfway houses in January 2020, just before the pandemic cut off client supply for several months. He didn’t receive his first reimbursement check until October. To keep himself afloat, he used his retirement funds and loans from family. And then turned to payday lenders.

He has been in trouble ever since, and recently he even missed his salary twice.

The crisis was averted on the 7th. The wire transfer from Amity Foundation finally arrived in his bank account at 3pm.

He said, “I immediately went to the bank, withdrew money and paid my employees.”

But food and electricity bills were mounting, and lenders were messaging them daily with offers.

“I just got one yesterday,” he said recently. “I’m in the process of paying off one I got in February or March. Just because the terms are so ridiculous, I opted out yesterday.”