Ninth grader Yaretzi Perez wants to become a neonatal nurse. But first she has to find a way not to miss so many days of school.

Her mother, Eleuteria Perez, is a single parent of five children — ages 17, 14, 13, 10 and 8. They attend four schools, all starting at the same time. She sometimes arranges to pick up the kids; sometimes pays someone to help. But the two older girls had to walk from their Arlington Heights apartment to their middle and high schools.

Years after COVID-19 upended U.S. schooling, things are back to normal in nearly every state. I’m still struggling with presenceThat’s according to data collected by The Associated Press and Stanford University economist Thomas Dee, whose research tabulated nearly 12 million chronically absent students in 42 states and Washington, D.C., for the 2022-23 school year, the most recent for which comprehensive data is available.

Nearly 1 in 4 students in California, or more than 1.45 million, were chronically absent in 2022-23, meaning they missed at least 10% of the school year — a rate comparable to the national average.

The statistics are even worse for the Los Angeles Unified School District, where nearly 1 in 3 students is chronically absent. Before the pandemic and even today, poor attendance is common in school systems with higher numbers of low-income families. In LA Unified, 81% of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, a common indicator of poverty in education.

The chronic absenteeism rate, while remaining high, represents an improvement from last year’s rate of 28.2%. Some states, including California, improved significantly; four states worsened. Before the pandemic, 15% of students were absent from school at least 10% of the time, which was considered very high at the time.

Though society has largely moved on from Covid, teachers say they are still grappling with its effects Schools closed due to pandemicAfter being at home for several months to a year or more, many students find school overwhelming, boring, or socially stressful. More than ever, children and parents feel comfortable staying home, making schooling even more difficult.

Schools are working to identify students whose attendance is falling, then providing them with help and trying to bridge the communication gap with parents, who often have no idea their child is missing school or away from school so frequently. Why it’s problematic,

To make more progress, experts say, schools will have to get creative.

School district staff decided the best solution for Yaretzi would be to get the family onto an L.A. Unified bus route, allowing the girl to commute to and from school.

Yaretzi Pérez, 14, with mother Eleuteria Pérez.

(Jason Armand/Los Angeles Times)

This decision was made as part of the LA Unified outreach A program called iAttendIn which district staff reach out to families or even visit them to find out why children are not attending school and then create solutions.

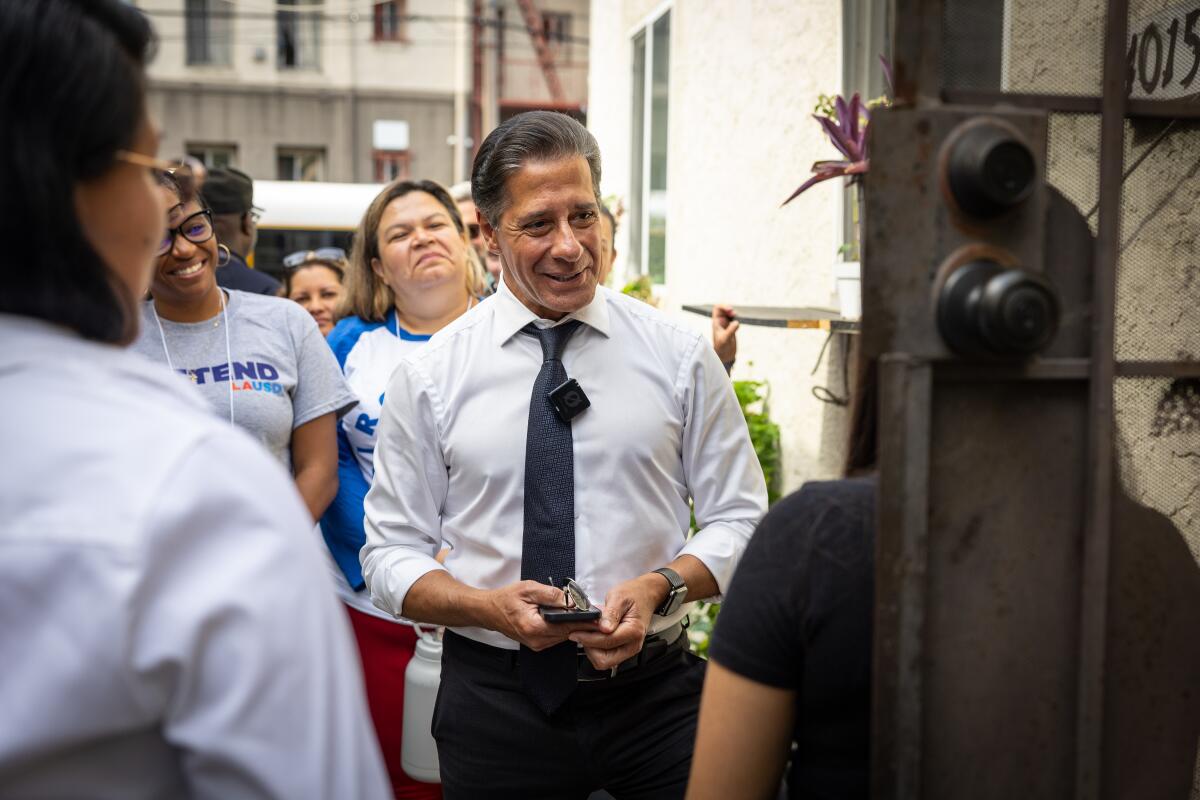

Superintendent Alberto Carvalho, who periodically conducts door-to-door meetings with the news media, said, “You have to meet students and families where they are, and for us, it’s about going to their homes.” In this case, the hope was that the publicity would have an impact on other families.

L.A. Unified Superintendent Alberto Carvalho, accompanied by senior school district officials and educators, visited Yaretzi Perez, 14, and her mother, Eleuteria, to offer support to the family and help curb their poor school attendance.

(Jason Armand/Los Angeles Times)

After talking to the daughter and mother, Carvalho handed the items to the students’ future teachers at L.A. High in Mid-Wilshire, which is about a mile from the family’s home. The teachers also handed out a bag of school supplies and a reassuring smile.

Yaretzi, who had been shy and overwhelmed for some time, eventually mentioned her interest AVID, a college preparation and support program for students who overcome challenges. She was involved in AVID at Cochran Middle School.

AVID and Algebra I teacher Sandra Ruiz encouraged this interest and pointed out a significant benefit, that Yaretzi would be with the same classmates for all four years.

“All the AVID classes, freshman, sophomore, junior, senior, are fourth period,” Ruiz said. “So make friends and then you can go on the bus with them.”

At LA Unified, about 45% of students were chronically absent in 2021-22. The following year, 2022-23, the national research’s comparable year, that percentage dropped to 36.5%. The initial rate for the 2023-24 school year shows improvement: 32.3%.

Caring adults – and encouragement

Across all Oakland districts and charter schools, chronic absenteeism rose to 53% in 2022-23 from 29% before the pandemic. The district asked students what would convince them to come to class. Students answered that money and a mentor.

The grant-funded program, launched in spring 2023, paid 45 students $50 a week for full attendance. Students also checked in with a designated adult daily and completed a weekly mental health assessment.

Zia Vera, the school district’s social-emotional learning chief, said paying students isn’t sustainable. But many absent students Lack of stable housing Or helping their families.

“Money is the hook that gets them in the door,” Vera said.

Vera said more than 60% of students’ attendance improved after participating. The hope is that the program will continue, along with efforts across the district that aim to give people a sense of belonging. Oakland’s African American Male Achievement Project, for example, pairs black students with black teachers who provide support.

Student who identify with their teachers Children are more likely to attend school, said Michael Gottfried, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. A study led by Gottfried stated, He said California students believe “it’s important for me to meet someone first thing in the day who is like me.”

A caring teacher made a difference for Golden Tachiquin, 18, who graduated from Oakland’s Skyline High School this spring. When she started 10th grade after a remote first year, she felt lost and anxious. She only realized later that these feelings caused her to feel nauseous and dizzy, which led her to stay home sick. She was absent at least 25 days that year.

But she connected with an Afro-Latina teacher who understood her cultural understanding and helped this A grade student realize that her low appearance did not define her.

“I had no fear going into her class,” Tachiquin said.

A similar situation is occurring across the country.

Flarentin “Flex” Jean-Baptiste missed so much school that he had to repeat his first year at Medford High, outside Boston. At school, “you do the same thing every day,” said Flex, who was absent 30 days in his first year. “It’s very frustrating.”

Then Principal Marta Cabral allowed students to play organized sports during lunch, somewhat like recess — if they attended their classes. She said high school students need freedom and the opportunity to move their bodies. “They’re here seven hours a day. They should have a little fun.”

Flex, 16, said Games for All “gave me something to look forward to.”

The following year, they cut their absenteeism in half. The number of students who were chronically absent from school dropped from 35% in March 2023 to 23% in March 2024.

Administrators at the high school are also expected to meet and talk with students each morning, especially those who are absent from school.

Stubborn conditions

Students who are consistently absent have a higher risk of illness. illiteracy and finally dropping outThey can’t even eat food, Counselling and socialization is provided at school.

Many of the reasons why students missed school during the early stages of the pandemic still persist: economic hardship, transportation Problems, Mild illness And Mental Health Conflict.

Emotional and behavioral problems can also cause children to miss school. University of Southern California Research has found The relationship between absenteeism and poor mental health.

For example, in the USC study, about one-quarter of students who were chronically absent had high levels of emotional or behavioral problems, based on results from questionnaires received from parents, compared with only 7% of students with good attendance. Emotional Symptoms in Teenage Girls In particular, many were related to missing school.

“These different things that we’re worried about are all interconnected,” said Morgan Polikoff, a USC education professor and one of the lead researchers.

How sick is too sick?

When long-term absenteeism in Fresno rose to nearly 50%, officials realized they had to revamp their pandemic-era mindset keeping kids at home,

“As long as your student hasn’t had a fever or vomited in the last 24 hours, you can come to school. That’s what we want,” said Abigail Ary, director of student support services.

Norida Perez, who oversees attendance, said parents often aren’t aware that physical symptoms can point to mental health struggles — like when a child doesn’t feel like leaving their bedroom.

L.A. schools Superintendent Carvalho caught some attention when he reversed COVID-era policies and emphasized the importance of keeping sick kids home.

“In some parts of our community, where COVID-related mortality rates were higher, the level of fear was higher,” Carvalho said. “Parents kept their kids home for any little runny nose.”

And many parents, Carvalho said, “exercise greater leeway in terms of attendance, where the parent almost gives up arguing with the child, especially if they’re a teenager…This is no longer acceptable. There is no substitute for a nurturing environment at school.”

Changing the culture regarding sick days is only part of the problem.

At Fort Miller Middle School in Fresno, where half of students were chronically absent, two reasons kept coming up: dirty clothes and lack of transportation. The school purchased a washer and dryer for families to use, as well as a Chevrolet Suburban to pick up students who missed the school bus. Overall, Fresno’s chronic absenteeism improved by 35% in 2022-23.

Melinda Gonzalez, 14, missed her school bus once a week and hitched a ride on a suburban bus.

“I didn’t have a car; my parents couldn’t drive me to school,” Melinda said. “Having that ride made a huge difference.”

Gecker is a reporter for The Associated Press. Bianca Vazquez Toennes, Sharon Lurie and Becky Bohrer of the Associated Press and Times staff writer Kate Sequera contributed to this story. Associated Press education coverage receives financial aid from many Private entities. Find AP Standards for charitable work, List Number of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.