It came to be known simply as “The Catch,” and it is perhaps the most recognized defensive play in baseball’s long and glorious history, the same play that made rising star Willie Mays famous.

It was the first game of the 1954 World Series between the Cleveland Indians and the New York Giants at the old Polo Grounds in New York.

The Polo Grounds, the Giants’ home field, was an old stadium reminiscent of a giant bathtub. The foul-line distances were short, 277 feet in left field, 258 feet in right, but the center-field fence, the far edge of the tub, was 455 feet from home plate.

Cleveland’s Vic Wertz, a left-hander, came to bat with runners on first and second in the eighth inning of a 2-2 tie, facing another left-hander, Don Liddle, who came in from the bullpen. Liddle, working a 2-and-1 count, threw a fourth-pitch fastball, and Wertz hit a three-run homer to center field.

Not at the Polo Grounds.

It is with great sadness that we announce that San Francisco Giants legend and Hall of Famer Willie Mays passed away peacefully this afternoon at the age of 93. pic.twitter.com/Qk4NySCFZQ

— SFGiants (@SFGiants) June 19, 2024

Mays, who was playing in shallow center field, missed the hit on the crack of the bat and sprinted with his back to the plate, caught the ball a few steps from the wall, caught it over his left shoulder, spun sharply and threw the ball back into the infield, losing his hat and balance in the process. The Giants escaped the inning without damage, then won the game in the 10thth on pinch-hitter Dusty Rhodes’s 270-foot pop-fly homer over the right field fence to lead to a game four victory.

Mays, who the San Francisco Giants announced Tuesday afternoon had died at age 93, had a stellar career as the flamboyant “Say Hey Kid” — some consider him the best of the best — but his name and “The Catch” are forever linked together.

He spent 22 seasons in the major leagues, mostly with the Giants in New York and San Francisco, leading the team to three National League pennants and one World Series championship. A center fielder who “could do it all,” Mays had a lifetime batting average of .302 with 3,293 hits, 660 home runs — which ranks sixth on the all-time list — and 338 stolen bases.

He played in a record 24 All-Star Games and won 12 Gold Glove Awards for his fielding. As shown in “The Catch,” his throwing arm was a cannon, and he did everything he could with aplomb, becoming as famous for his basket catches as he was for catching runs out from under his cap, both in the field and on the basepaths.

Hall of Fame member and longtime broadcaster Joe Morgan, a contemporary of Mays, said, “Willie Mays is the greatest player I ever saw. … He did something every day on the field that made you say, ‘Wow!'”

Leo Durocher, who spent a lifetime in baseball as a player and manager, and was Mays’ first manager with the Giants, declared his pupil “the greatest ballplayer that ever lived”, and Durocher had seen Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio, Ted WilliamsStan Musial and Hank Aaronamong other dignitaries.

Sportswriter John Shea talks to Willie Mays in the San Francisco Giants clubhouse at Oracle Park.

(Brad Mangin photo)

Mays’ assessment? Speaking to the Contra Costa Times in 2004, he said, “There have always been people who said I was better than Babe Ruth, better than Aaron. I don’t have any problem with that. … (But) that’s not why I played baseball. I played baseball so I could enjoy what I did; the fans enjoyed what I did, and that was good enough for me.”

“I’ve always let other people make the decisions,” he told the Times in 1979. “But when you look at it, there are better hitters than me, better runners, a lot of people who could have done it. Some? better things than me, but I was a complete player. That’s the key word, Complete.”

Whether or not he was the best is a debate for the ages. What cannot be debated is that, as a man born to play baseball, he generated admiration and controversy in almost equal measure. He was so popular in New York, where he played stickball – a form of baseball using a broom or mop handle and a rubber ball – with neighborhood kids in the streets of Harlem before moving to the ballpark, that when the Giants moved to San Francisco in 1958, he was greeted with a lot of coolness. And when he was traded to the New York Mets late in his career, many said, “Well done!”

His casual “hey say” reply to anything Some considered this greeting spontaneous and natural, while others considered it a tactic for a man who could not remember names. He was praised for his showmanship and reviled for hotdogging, when his too-small hat often flew off with a flick of the finger. And while some were thrilled by his running basket catches, others accused him of making routine play difficult.

At a time when black players were finally trying to make it in a sport that had long been a white-only sport, he endured racist taunts, but others criticized him for not speaking out more forcefully about how the sport and fans mistreated black players like him. Always under a lot of stress, he suffered mysterious fainting spells and panic attacks, leading some to question his dedication.

Through it all, Mays played baseball until he was 40.

“I’ve just been playing ball since I was 6 years old,” he once said. “I’ll never understand why some guys make baseball out to be a hard-working sport. To me, it’s always been nothing but fun. … My dad played semipro baseball when I was a kid in Alabama, and I remember the biggest surprise of my life was the day I found out people paid him to do it. I thought it was the coolest idea anybody ever came up with — like getting paid to eat ice cream.”

William Howard Mays Jr. — his father was named after former President William Howard Taft — was born in Westfield, Alabama, near Birmingham, on May 6, 1931. His parents divorced when he was of school-going age and he went to live with his aunt, but his father, who worked in a steel mill and was an outfielder for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro National League, checked on him regularly and made sure young Willie was getting a proper baseball education.

When he was 10, he played sandlot games with boys four or five years older and joined his father’s steel mill team as a pitcher at age 14. In 1948, his father introduced the 17-year-old Mays to Black Barons manager Lorenzo “Piper” Davis, who drafted the young player, then signed him to a $300 contract for one season.

Mays played home games and weekend road games for the Black Barons during school, then played full-time in center field during summer vacations, soon attracting the attention of major league scouts. On June 20, 1950, his high school graduation day, he signed with the Giants for a $6,000 bonus.

The Giants sent him to Trenton, N.J., in the Class B Interstate League, where he hit .353 in 81 games, then sent him to Minneapolis in the Triple-A American Association at the start of the 1951 season. In 35 games with the Millers, he batted .447 with eight home runs, and his Minor League days were over.

After a poor start and looking for a boost, the Giants called him up and, despite his protests that he wouldn’t be able to hit against big league pitching, inserted him into the starting lineup.

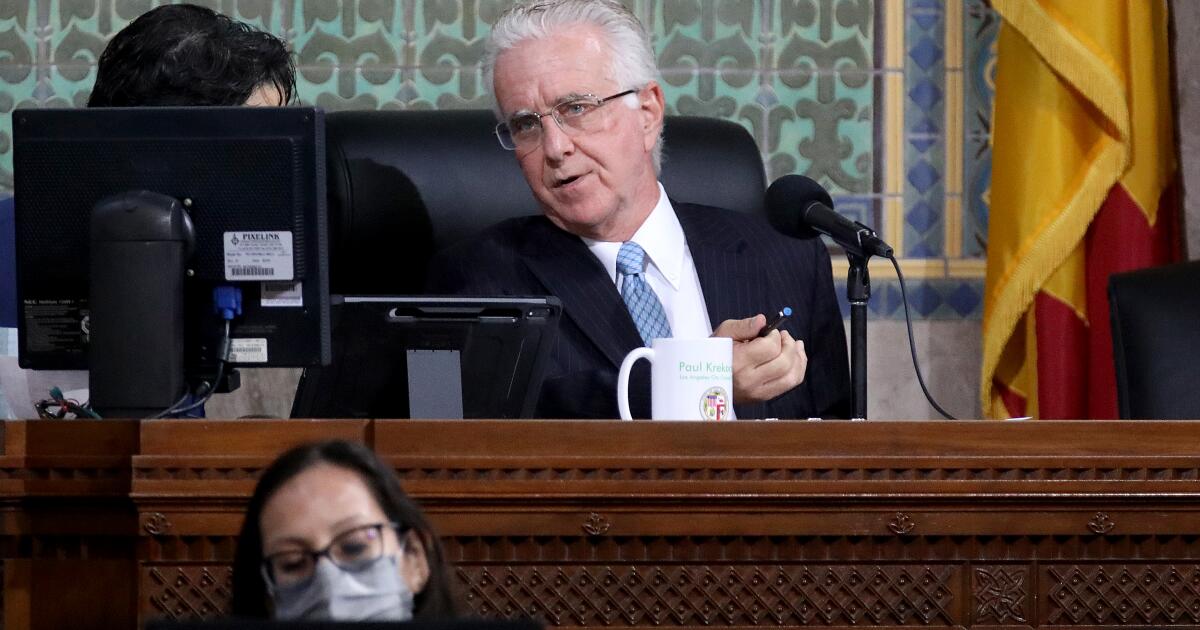

Willie Mays with his arm around Mickey Mantle.

(AP)

Eventually, his stature grew so much that there was a debate among New York fans over which of the local teams had the best center fielder: the Giants had Mays, the Yankees had Stephen McGraw, and Stephen McGraw was the new center fielder. mickey mantle Or with the Brooklyn Dodgers Duke SniderBut his debut was less than sensational. He had only one hit in his first 26 at-bats, a home run off Warren Spahn of the Milwaukee Braves. and asked Durocher to send him back to Minneapolis.

“You’re going to play center field for me tomorrow and the day after that, so you better get used to the idea,” Durocher replied. “I don’t care what you hit, I’m not sending you down.”

Brimming with confidence, Mays turned his and the Giants’ season around. He hit .274 with 20 home runs, and the Giants, who were 13 ½ games behind Brooklyn in mid-August, came back to tie the Dodgers for the pennant on the last day of the season, forcing a three-game playoff. Mays was on deck in the ninth inning of the third game when Bobby Thomson Hits “The Shot Heard Round the World”, a three-run homer that clinches the National League championship for the Giants.

That surge culminated in the World Series, which the Yankees won in six games, but Mays was on his way and Durocher gave him full credit. “Mays was the spark,” he said. “When it looked like we couldn’t win, he put us on his back. He put the whole team on his back.”

Mays’ path was, well, to go into the Army. He was drafted in May 1952, spent the next two seasons playing ball in a khaki uniform, then was discharged in March 1954, having the best season of his career. He hit a league-high .345, hit 51 homers and drove in 110 runs, leading the Giants to five games ahead of second-place Brooklyn, then beat the Indians in the World Series.

Mays led the Giants to another World Series in 1962, batting .304 with 49 home runs and 141 RBIs, but by then the team had moved to San Francisco, where he couldn’t connect with fans the way he had in New York.

Playing center field at wind-torn Candlestick Park was always a tough job, and although Mays did it well, was always a home run threat, consistently hit over .300 and was widely recognized elsewhere as a first-rate star, he was still considered by many in San Francisco as, at best, pretentious and aloof at worst, preferring to lavish affection on the Alou brothers, Jesus, Matty and Felipe; Juan Marichal; Willie McCovey; and others.

Baseball Hall of Famer Willie Mays in the documentary “Say Hey, Willie Mays!”

(HBO Sports Documentary)

However, in tribute to Mays today, a giant bronze statue of him is installed at Willie Mays Plaza at Oracle Park in downtown San Francisco, and he was inducted into the Hall of Fame as soon as he became eligible.

In May 1972, the 41-year-old Mays was traded back to New York, where, well past his peak, he spent two forgettable seasons with the Mets. He played in another Bay Area World Series following the ’73 season, his last, but baseball followers, purists and casual fans alike, shuddered watching the former style master stumble around the Mets’ outfield against the Oakland Athletics, who repeated as champions in seven games.

“Growing old is a helpless agony,” Mays said later, and later admitted ruefully that he had overextended his career by about two seasons.

After retirement, he worked intermittently for the Mets and Giants and eventually signed a lifetime public relations contract with the Giants in 1993. He was out of baseball for six years, however, because then-commissioner Bowie Kuhn, unhappy with any connection between baseball and gambling, banned both Mays and Mantle because they took public relations jobs with Atlantic City casinos.

Both were reinstated after Peter Ueberroth replaced Kuhn as commissioner in 1985.

Mays’ wife of 41 years, Mae Lewis, died in 2013. He is survived by son Michael.

Kupper is a former Times staff writer