In recent years, this discussion has become even more intense with the proliferation of streaming platforms, giving more space to certain works that are considered ‘controversial’. Some argue that filmmakers are ‘rewriting history’, while others believe that ‘creative freedom should have no limits’. It is an ongoing debate that questions the boundaries between art and responsibility.

How much creative freedom is too much?

Directors, actors, and industry insiders have very different views on how much creative freedom filmmakers should have when it comes to historical films. While some advocate “complete creative freedom,” others emphasize the importance of maintaining a sense of “responsibility” to historical facts.

Film Producer Sudhir Mishra argues that creativity should flow freely without any restrictions. “As long as it is not promoting violence, or inciting hatred, anything should be allowed to happen through your cinema,” he says, adding that he believes filmmakers should have the freedom to tell their stories the way they want. “We are getting too sensitive,” comments Mishra, and warns that stifling creativity will lead to a state of intellectual stagnation. “Whether it is ‘Kerala Story’ or ‘The Kashmir Files’ or my film ‘Rumours’, everything should be allowed to happen. I think, we are getting too sensitive. If you stifle the creativity of young people, they will stop thinking,” he says.

Meanwhile, the writer and director Siddharth P MalhotraTaking a more nuanced approach, some warn against distorting facts while acknowledging the need for creative freedom. “Creative freedom to improve the movie theatre experience without distorting facts – that much should be allowed,” Malhotra insists. He says filmmakers have a responsibility to respect the essence of the historical material and entertain the audience without tampering with the “soul” of the story.

On the other hand, Joachim Rønning, director of films like ‘Maleficent: Mistress of Evil’, emphasizes the importance of being true to the story. He highlights that although certain aspects of a character’s life may need to be edited for the narrative arc, the goal should be to stay as close to reality as possible. “I think it’s very important to be truthful,” he says.

In contrast, Suman Kumar agrees with this view, emphasising the absolute nature of freedom in art. “There should be no conditions imposed on it. Freedom is absolute.” He believes that filmmakers should be allowed to “speak the truth” and that restrictions can undermine the integrity of storytelling.

Balancing fact and fiction

The delicate balance between storytelling and historical accuracy is also an ongoing concern in show business. Filmmaker Apurva Asrani acknowledges the difficulty of staying true to both, saying, “There are certain things you can make up and then there are facts you need to stick to.” Like Malhotra, Asrani believes that while filmmakers can imagine aspects of a character’s personal life, they must stick to the larger, more public facts of historical events.

For actors like Iwan Rheon, the difference between then and now complicates the portrayal of history. He says it’s important to strike a balance between accuracy and present-day sensibilities. Reflecting on his TV show Those About to Die, set in Rome 79AD, he says, “I think what’s important when you’re watching something based on history is that by today’s standards we consider things that are morally horrible, which certainly weren’t horrible back then. Yes, there were horrible things going on, but it’s a different time. And we try to learn from history.”

This tension between historical fidelity and creative expression is echoed by actor Rhys Ifans, who played the infamous historical figure Rasputin in ‘The King’s Man’. For him, embodying a historical character is an act of interpretation and subversion. “We are allowed, in cases like this, to embellish and shape the character,” he says, adding that the fun comes from the space given to actors to reimagine their roles within certain bounds of truth. “I found playing Rasputin very liberating. Visually, with a big wig and beard, it acts like a mask and frees you up. To fulfill your innate sense of mischief and subversion, that’s so much of it,” he said.

An increasingly intolerant audience

There has been growing public outrage over certain films in recent years, with many in the film industry believing this reflects a wider climate of intolerance towards artistic expression. “I don’t think we should give in to these things. It’s wrong. The state should take care of people who make cinema. It’s an expensive medium,” says Sudhir Mishra. He feels that despite a mechanism in place to review films, outside forces are exerting too much influence on how films are viewed. He adds, “I don’t think anyone other than the anti-constitutional people should react. Because then anyone can react to anything, there’s no limit.”

In contrast, Suman Kumar takes a more optimistic view. He believes that storytelling requires honesty. “If you are honest about it I don’t think you will face trouble.” For Kumar, artistic interpretation is inherently subjective, and the audience’s interpretation often strays far from the creator’s intent. “Any work of art is open to interpretation,” he says, suggesting that controversy often arises from a fundamental discrepancy between the filmmaker’s vision and public perception. “I have read that this particular show or film got into trouble, but I personally don’t think there should be any interference.”

The role of disclaimers in protecting artistic freedom

Disclaimers have become a vital tool in treading the fine line between artistic freedom and public sentiment, especially in historical films and series that have been mired in controversy. They are often seen as safeguards, allowing filmmakers to explore sensitive subjects while distancing their work from direct claims of factual accuracy. As seen in projects such as ‘IC 814: The Kandahar Hijack’ and ‘The Kerala Story’, disclaimers serve to prevent backlash by clarifying the elements of fiction or the interpretive nature of the content. However, their effectiveness in guarding against public unrest or legal challenges is limited. While they may offer legal protection, filmmakers such as Siddharth P Malhotra and Apurva Asrani agree that disclaimers do little to prevent criticism or controversy

Malhotra, who is more skeptical about the power of disclaimers to protect filmmakers, believes they serve a legal function but ultimately cannot protect creators from criticism. “Disclaimers cannot protect filmmakers from controversy,” he states categorically and adds, “It serves to tell people that the film is not made to offend anyone.”

Suman echoes this view, and considers disclaimers a mere technicality. “They can protect you legally. You can claim ‘we have already shown this disclaimer’. If people are offended by something, it doesn’t matter whether you have given a disclaimer or not, they will get offended,” he says.

On the other hand, Sudhir Mishra questions the effectiveness of disclaimers, arguing that they often benefit those who deliberately create trouble, “Why should disclaimers not work? I think because we are encouraging those who create trouble.” Recalling the uproar during the release of his film Tamas, he says, “People do not create problems, some vested interests do. I have been a victim of all this personally, we were thrown out of the theatre and the industry stood and watched.”

Interestingly, Apurva adds another layer to this debate, suggesting that while disclaimers may work in some cases, “if you are marketing a film by capitalising on ‘real events’, you should also be prepared to face questions.” For him, the balance between factual accuracy and artistic interpretation lies in how stories are framed, especially in politically sensitive times.

politicization of cinema

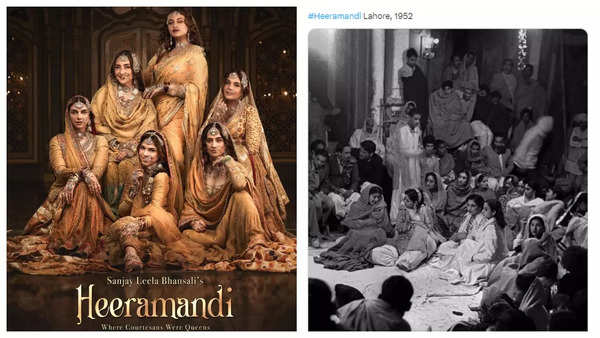

Political and fringe groups in India have repeatedly targeted Bollywood filmmakers over alleged ‘misrepresentation’ of history, religion or social issues. These groups often resort to legal action, protests or even threats of violence to prevent film releases. One of the most infamous examples is the Karni Sena’s violent opposition to ‘Padmaavat’ (2018). The group claimed the film distorted the image of Rajput queen Padmavati, leading to physical attacks on the film’s director Sanjay Leela Bhansali and vandalism on the film’s set. Actress deepika padukoneRani, who played the role, received death threats, including a threat of a bounty on her head.

Similarly, last year itself, political groups had created a controversy over the song ‘Besharam Rang’. Shahrukh KhanSome political groups have ordered a ban on the film ‘Pathan’ due to Deepika Padukone’s saffron bikini in the song.

Other films like ‘Jodhaa Akbar’ (2008), ‘Ae Dil Hai Mushkil’ (2016) were mired in political controversies. Director karan johar He also had to apologize for casting Pakistani actor Fawad Khan in the film during a time of rising tensions between India and Pakistan.

Other examples include filmmakers being ordered to change the titles of their films and character names just before release to avoid legal action and adverse reaction.

Politicisation of cinema has become an inevitable reality in today’s scenario, where historical narratives and sensitive subjects are often subjected to political scrutiny. This in turn has a significant impact on the creative process, especially on historical films. Malhotra is candid that filmmakers are often restricted in what they can portray, even in biopics. Citing the example of his film ‘Maharaj’, based on Indian journalist Karsan Das, he says, “There is a lot about Karsan that I cannot say, there is a lot about the story that cannot or should not be told.”

He added, “I don’t think I have fulfilled Karsan Das’ life the way it should have been. He was a great human being and there were a lot of prejudices and preconceptions about him, which is why things turned out the way they did. I am glad that people still appreciated the film and it was universally declared a hit.”

Elaborating on the challenges of telling stories based on true events, he said, “There are a lot of emotions involved and when you are telling a historical or a biopic, everybody’s feelings have to be taken into consideration because it is related to a person or some emotion or sentiment.”

Echoing this sentiment, Asrani says that different governments impose different restrictions on storytelling. “10-15 years ago, no one could make a film that was critical of ‘Emergency’, but today there is freedom to do so,” he says, explaining how the political climate directly affects the stories filmmakers tell.

The debate over creative freedom in show business is still far from settled. While some argue in favour of complete artistic freedom, others insist on the need for restraint in dealing with historical narratives. As films continue to push the boundaries of storytelling, the line between creative expression and historical distortion remains controversial.

Heated exchange of words between Anubhav Sinha and journalist over ‘IC 814’ controversy