Oh-so many millennia ago, the Palos Verdes Peninsula emerged from the sea like Aphrodite, beautiful and dripping wet.

ok, so it didn’t happen Absolutely that way. The uncanny workings of geology – with a fanciful nod to Poseidon, god of earthquakes and the oceans – created the stunning headland that juts its chin out into the Pacific from Los Angeles County.

And geology has also had a hand in its recent slippery dangers. (Poseidon: Don’t blame me, mortal!)

As winter rains finally get back to where they are for the summer, the peninsula could match its casualty list from the last eight or nine months.

Chiefly and most recently, the dazzling Wayfarers Chapel, Lloyd Wright’s wood and glass marvel in Rancho Palos Verdes, a National Historic Landmark, always seems to loom above the ocean. Now it’s sadly leaning towards it: it’s closed, and probably United NationsLikely to reopen at same location Anytime again.

A few months ago, homes in Rancho Palos Verdes were red-tagged. Landslide system at Portuguese Bend Pressing the accelerator. As John Cruikshank, the mayor of Rancho Palos Verdes, mournfully described it, the land “used to move inches a year; the land used to move inches a year; now it moves feet all year long.” Last year, 10 Homes in Rolling Hills Estate catastrophically collapse into valley,

News bulletin

Get the latest from Pat Morrison

Los Angeles is a complicated place. Luckily, there is someone who can provide context, history, and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional materials from the Los Angeles Times.

No place in Los Angeles County’s spectacular 4,000-plus square miles – desert, mountains, beaches, hills and basins – has been unaffected by what I’ll call “late-stage flooding,” but in the heights of the Peabody Peninsula , it was dramatic and Costly,

The place that looked like an eternal fortress is transformed into feet of clay – and I mean that literally, as you’ll see.

The peninsula’s human history has been brief compared to its geology. Native Americans built their villages in this province, and Málaga Cove has been a settlement for at least seven millennia. On October 8, 1542, four days less than 50 years after Columbus landed in the New World, a Portuguese explorer whose name in Spanish was Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo sighted the Pivi Peninsula. Perhaps he deserves the title of “Father of Smog”, as he called the place “Bay of Smoke”, perhaps from the signal fire built atop the headland by Native Americans.

A few centuries or so later, the peninsula became Part of the Spanish land grant, and the demise of Manuel Dominguez as his Rancho San Pedro. Later, in Mexican California, another aristocratic family, the Sepulvedas, became owners of the land now named Rancho Palos Verdes.

A whaling station operated here for a short time and by the 20th century, the cattle that once grazed the province had long disappeared, but people kept visiting.

1

2

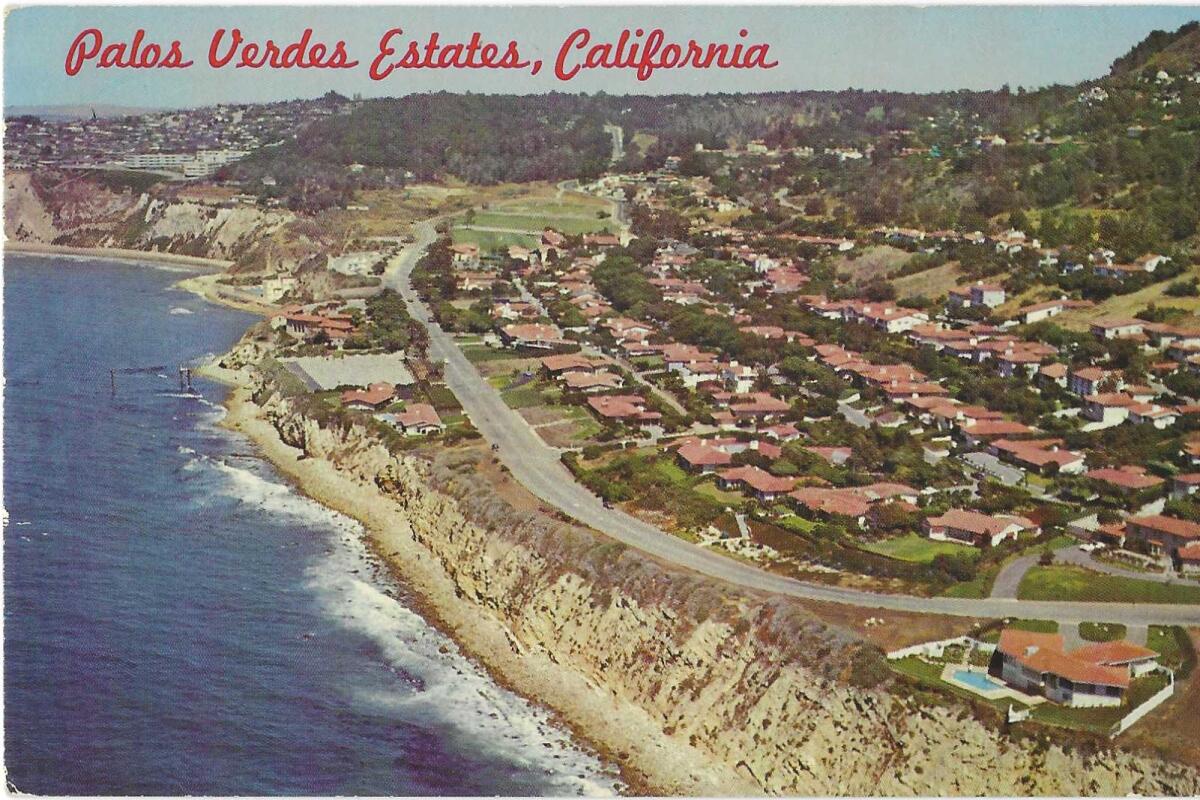

1. An old postcard from Pat Morrison’s collection shows the lush hills of the Palos Verdes estate before development brought thousands of homes to the peninsula. 2. Another postcard shows the quintessential terracotta roof tiles of Palos Verdes Estates. This also reflects the precariousness of some houses that have tiled roofs.

Around World War I, named after an influential financier Frank Vanderlip Visited the site and was so impressed by its beauty that he began planning to acquire and develop the peninsula, a sort of Newport of the Pacific, a California version of the Rhode Island community where Gilded Age magnates quarried marble by the sea. The “cottages” were built and gilt. Vanderlip built his own fabulous wealth, Villa Narcissa, in the 1920s. A few years ago, I was the guest there for lunch, along with an English friend who had been invited Grand Dame Daughter-in-law Elaine of Vanderlip,

In the 1930s, locals held foxholes and hunting balls and other fashionable celebrations, yet it was not until the next World War that the peninsula became filled with more modest homes in truly luxurious settings. Homes are still modest, certainly in comparison metabolically exaggerated mansion of Beverly Hills and West LA, but now the prices, like the views, are spectacular. The supporting cast has been on the run for years Marineland (now discontinued), aggressively territorial surfer gang, wild peacockAnd the inevitable golf course, one of them is donald trump,

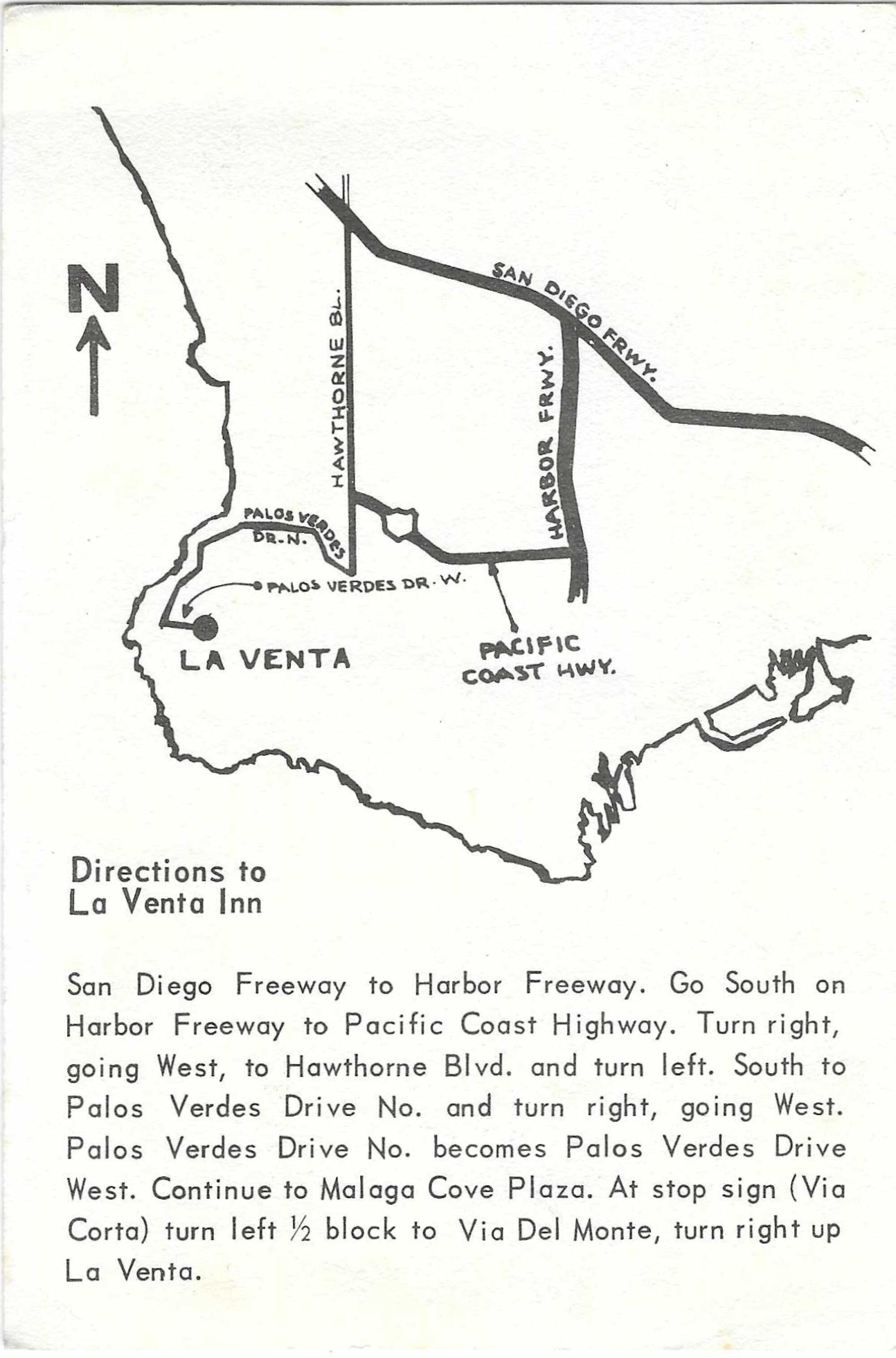

An old postcard from Pat Morrison’s collection directs drivers to the La Venta Inn, which remains a wedding venue, and shows the outline of the peninsula’s coast. Don’t miss a single turn.

It’s a Twitter-short summary of human history.

For the geological lineage that gave rise to today’s fragmented Palos Verdes Peninsula, I consulted Kevin Coffey, a lecturer in Earth, planetary and space sciences at UCLA.

Coffey lives on the peninsula and is happy to have its real-life science outside his door: “The Palos Verdes Peninsula is unique in its geology in many ways. And in other ways it’s the geology we have in much of Los Angeles, but it’s unique in how it’s elevated, how we can see all of it.

Where Los Angeles is now, there was only the ocean. LA County Museum of Natural History LA Underwater Exhibition Takes us back 90 million years to life in underwater L.A. So the ocean, not space aliens, explains why ancient whale parts have shown up in Lincoln Heights and Mount Washington, on what was once the outline of the ocean floor Were.

Even after the peninsula recovered from those eras of submergence, about a million years ago, for a few centuries, it was still an island for a very long time, like its closest relative, Santa Catalina. A stream of water separated it from the continent. Only about 75,000 or 100,000 years ago that waterway silted up and filled in, and lo and behold, the province was connected to the mainland.

One thing that pleases Coffey about PVP is that it is made of all three types of rocks – sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous.

If you cut it like a cake, you get this:

On top, like frosting on a cake, is the shale soil, Altamira shale, the sedimentary legacy of those maritime millennia. These layers have mouth-watering names that sound like expensive paint colors or elaborate pastries: Valmonte Diatomite, San Onofre Breccia, and the PV specialty, Málaga Mudstone. Combined, it’s “a few hundreds of feet deep,” says Coffey, which sounds huge to us, but geologically it’s about as thick as nail polish, and all originally clay that piled up on ancient sea floors. It got compressed and turned into rock.

The base layer of the PV cake is Catalina Schist. We’re All Living on Catalina Schist, which is a great name for a band. It’s this strong metamorphic rock that forms the base of the Los Angeles Basin, “the foundation of this entire region,” says Coffey. It’s far below, below us garden And freewayAnd the one place on the mainland where you can see her naked as a newborn baby is in Palos Verdes, a natural preserve and canyon known as the Pacific Ocean. george f, (Who was the George F. who became so immortal? No one knows for sure – The Daily Breeze suggested That it was either early land businessman George S. Bixby’s name was an incorrect transcription, or George F. Vickery, an old San Pedro rancher.)

But hidden in the snake’s nest of sedimentary layers are slippery slopes that are responsible for a large portion of what falls: volcanic ash.

Nice view (on an old postcard from Pat Morrison’s collection) – if you can buy it.

Now if you were awake in high school science class, you might be thinking, igneous rock: volcanic lava. solid stuff, so solid that Icelandic architect is suggesting Using lava as a building material. The volcanoes located some distance away left behind some strong volcanic rocks, but also this gust of volcanic ash was swept under water even before the Peevy Peninsula came into existence.

Volcanic ash is quite different from lava, so it can be blown around. Underfoot and underground, it is playful. When it’s wet, it turns the coffee into what’s called “clay soil” which can be as smooth as a water slide. And on Palos Verdes, Coffey says, that’s what it does: When water seeps through the frost of the shale, part of what Coffey calls “sedimentary veneer” from those underwater eras, and then a layer of volcanic ash. Hitting these deposits, the veneer can start sliding like Buster Keaton on a banana peel, and take whatever is sitting on top of it with it.

oh, and then there were Earthquake,

Much of Southern California finds itself near the rugged intersection of the North American and Pacific plates, the boundary of which we know as the San Andreas Fault.

This is a strike-slip fault, you get seismic action when these plates slide past each other. But when a fault bends itself, you get serious plate-to-plate contact, the kind of earthquakes that shook the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains (I’m thinking of the uplift as a geologic push-up bra. Am).

The Peabody Peninsula is a long way from the San Andreas, but L.A. is still surrounded by a network of small, connected faults—some of them as jagged and dramatic as the silhouette of a lightning strike. These are those who helped shape the peninsulaSqueezing the land into twists and turns and bends.

By comparison, Coffey says, “If you go to Torrance, Carson, you have the same rocks of the Palos Verdes Peninsula under your feet – they’re still down there because nothing has happened to push them up.”

Landslides have been occurring on the peninsula since it became land, so there is nothing new in the hazards from last year. According to Coffey, the Portuguese Bend area is “so old that it has gone through several ice ages.” These cycles cause the earth to slide when it is wet, and then stop or slow down when the ground dries. What’s new to the recipe is what we humans have added to it: the weight of homes and roads, and water pumped into the ground from the landscape irrigation and septic systems of PV peninsula cities.

But right now, the late spring weather forecast for temperatures and precipitation looks remarkably like the peninsula: high and dry.