When Bill Keener began working as a field biologist at the Marine Mammal Center in the 1970s, there were no whales or dolphins in San Francisco Bay. The waters east of the Golden Gate Bridge teemed with life — sea lions and harbor seals abounded — but not a single cetacean was in sight.

Things started to change in the late 2000s.

Now four cetacean species live in or regularly visit the busy waters east of the Golden Gate — harbor porpoises, gray whales, humpback whales and bottle-nosed dolphins.

Yet Keener and other marine researchers aren’t sure whether the animals’ presence is a sign of ecosystem health and rejuvenation or a harbinger of planetary disaster. And in each case, the story is a little different.

Bill Keener watches gray whales from a viewpoint at the Marin Headlands in May.

(Lorraine Elliott/For The Times)

Whatever the reason for their return, they are concerned that as the numbers of these fascinating giant creatures grow, so does the risk of them being injured and killed in these busy waters.

“We have one of the busiest ports on the West Coast, 85 private and recreational marinas, high-speed ferries and a lot of ship traffic,” said Kathy George, director of cetacean conservation biology at the Marine Mammal Center. “These animals are showing up in places where it’s cause for celebration, but it’s also cause for concern.”

Harbor Porpoise

Take, for example, the Port Porpoise (submarine).

Keener said these friendly, blunt-nosed, dolphin-like animals were a permanent fixture in the bay for thousands of years — until they were wiped out.

A World War II-era photo shows military ships in San Francisco Bay.

(Bettman Archive)

Evidence from Ohlone shell mounds — huge piles of discarded bones and shells found throughout the Bay Area — indicates that though they were once abundant, they either died out or fled en masse in the 1940s when the U.S. beefed up its defenses during World War II. Fearing enemy submarines, the Navy strung a huge steel net across the Bay to prevent underwater boats from penetrating.

Whether it was the physical presence of the net, or the clanking and noises it made underwater (which Keener said was a huge mistake). possibly very loud), the porpoise disappeared for more than 60 years.

What brought them back isn’t entirely clear. It may be partly due to the effectiveness of gill-net bans in the 1980s, which allowed the porpoise population to grow. They may also have been following food sources. And once the porpoises entered, they recognized it as a very good place to settle.

Whatever the reason for bringing them here, they’ve stayed here — and they’re a common sight splashing and diving in the water along the shores of Kirby Cove or around the Point Diablo Lighthouse peninsula.

humpback whale

Last year, a humpback whale fluke was spotted emerging from Monterey Bay.

(Brian Van Der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Humpback whales may also be good news – although, unlike porpoises, they were probably never permanent residents of San Francisco Bay. There is no evidence of them in the shell mounds and no historical reports of them inside the bay.

But they have been consistently present off the coast – migrating from their wintering areas in Mexico and Central America to California in the summer, where they feed on fish and krill along the coast. However, as a result of whaling, their numbers had fallen to about 2,000 by the early 1970s.

However, since then their population has increased to 20,000.

“That’s what happens when you stop hunting them,” Keener said.

And in 2016, no one remembers the first time a flood of humpbacks came to the bay after a dense brood of anchovies. Since then, they have been regular visitors during the summer.

Gray whale

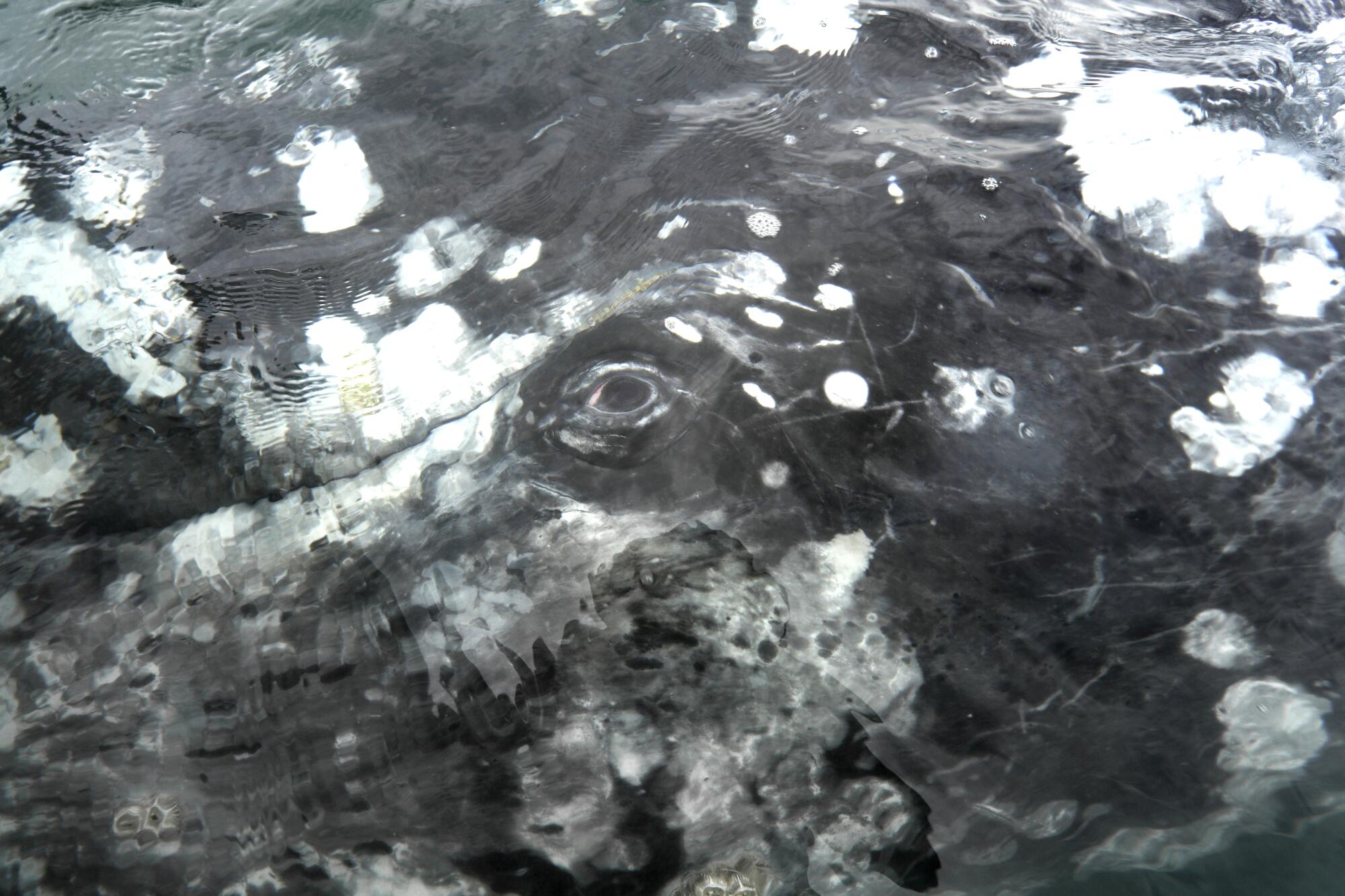

A gray whale surfaces with open eyes above the water in Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California, where the species goes to give birth and feed its young.

(Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times)

The story of the gray whale may be a little more ominous.

Like humpback whales, there is no historical record of any major historical presence of these singing whales in San Francisco Bay – other than a single skeleton discovered in a 2,500-year-old shell mound and a historic report from Spanish missionaries about gray whales living in the bay.

But they stopped appearing in 1999 — right around the time an unusual mortality event began that culminated in 2002 in cutting the eastern Pacific gray whale population by nearly half.

When the mass bird strandings subsided and their numbers began to increase once again, they were never seen again – except for once or twice a year – until 2019, when another mass mortality event occurred.

This time, however, whales appear to be nearby. 16 whales have been spotted in the bay this year – including who died,

Marine Mammal Center interns Nicole Crystals (left) and Noreli Faz, working under NOAA permit number 24359, dip a GoPro camera into the water to identify a dead gray whale in San Francisco Bay near Richmond last month.

(Lorraine Elliott/For The Times)

But this time, they’re doing something that Keener and others say is a little unusual: They’re serving meals.

Typically, gray whales feed in Arctic and sub-Arctic waters only during the summer months, when the cold sea floor teems with life and millions, if not billions, of tiny shrimp-like creatures that the whales capture in their huge jaws. The whales feed throughout the summer, and only then make the 6,000-mile journey south to Mexico, where the females give birth and nurse their young in a warm and protected inlet along the Baja Peninsula.

Once they leave the Arctic, they do not feed until the following year.

But researchers and observers have seen them diving and looking for food in San Francisco Bay — as well as lunge-feeding, a style of eating by humpback whales in which they open their mouths and swoop down to the water’s surface to catch fish and other creatures.

And while this might be a worrying sign — that their usual grazing grounds are no longer productive, possibly as a result of the extreme climate changes taking place in the Arctic and ocean — Keener prefers to look at it in a more positive light.

This feeding behavior “is an indication that these guys were probably hungry, and they were looking for other sources of food,” he said, citing his colleagues’ autopsy research on stranded whales that showed a large number of them were malnourished. “But it also shows that they’re resilient, and they can change their behavior and do something they’re not known for. That’s a really good sign.”

The animals survived dramatic climate changes, such as the ice ages, Keener said, and this resilience “may have helped them cope with the ice ages and all the environmental changes that have occurred in their feeding grounds over the last several thousand years.”

This bodes well for the species, he said, as climate change affects vast ecosystems across the planet.

And, he said, his work is showing that it’s not just random whales that stop by during their migration. Some whales are returning repeatedly, leading him and his colleagues to think “some of them are learning our local area, figuring out how to navigate and find food. You know, just living in our area.”

bottlenose dolphins

The now-frequently-reported bottlenose dolphins may also be one of those ray of hope stories.

Normally considered a warm-water species found in Southern California, this species began arriving in San Francisco Bay around 2008 – like the porpoises. Their range began expanding northward (following initial periods of intense ocean upwelling) around the 1980s. El Nino occurrence), and by 2000, they began to be observed with relative frequency in coastal waters near the bay.

Keener said there are no resident groups inside the bay, but “they come by.”

Keener said the Marine Mammal Center has compiled a local photo-identification list that includes 120 adults. Some of them have been identified as dolphins that lived in Southern California in the 1980s. He said the dolphins continue to hang around — a known female dolphin was seen roaming the waters off Monterey in the spring, and just last week another was seen hanging out around the Sea Ranch in Sonoma County.

“She really moves around, and that’s normal,” Keener said.

The big picture in Busy Bay

A speedboat cruises through San Francisco Bay. Ship collisions are one of the biggest threats to marine life.

(Lorraine Elliott/For The Times)

And though this observer of the rapidly changing ocean and the unusual behavior of its inhabitants is hopeful on a larger, existential scale, he — and others — are concerned about the more immediate safety of these fascinating sea creatures in the busy shipping routes of San Francisco Bay.

He said none of these animals are on the endangered species list, but that doesn’t stop him and his colleagues from worrying, “especially if they come into the Gulf, where it’s dangerous for them. There’s a lot of ship traffic.”

George, of the Marine Mammal Center, said there are vast stretches of water in the Gulf region with no voluntary ship speed reduction zones — a tactic that conservationists, ports and shipping companies have used elsewhere to reduce the chance of ships striking cetaceans.

News bulletin

Our oceans. Our public lands. Our future.

Get ‘Boiling Point’, our new newsletter discussing climate change and the environment, and be part of the conversation – and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional materials from the Los Angeles Times.

But George said he and other conservationists are working on it with the Harbor Protection Committee, which he says has been receptive and is working on formalizing a plan to protect the animals.

“I am very excited about the collaborations that are taking place and their continued evolution,” he added.